Perhaps also for this reason, most of the exercises for the pectorals are based on a "high expression of strength which, as we know, is - in absolute terms, but not relative to body weight - greater in males than in females (adulthood). .

But how much does force really affect the conformation of the pectorals? And vice versa, to what extent is the size of the pectorals capable of determining the capacity for strength? So, are all chest exercises the same? If not, why? Is it possible to stimulate the pectorals in a sectorial way, making them grow more above, in the center or at the bottom?

To learn more: 4 exercises to strengthen the upper body or pectoralis major, the large superficial muscle - just below the breast - which forms each of the two symmetrical sides of the chest (divided on the sagittal or longitudinal axis). Note: actually, in this anatomical site, but at a lower loggia - deeper - the small pectoral also helps to determine the thickness of the chest pectoralis minor - even if in a rather low percentage.

The pectoralis major is a fan-shaped muscle. It originates anterior to the clavicle (sternal half), from the anterior sternum, from the cartilage of the sixth or seventh rib, from the cartilages of all true ribs - often with the exception of the first or seventh - and from the aponeurosis of the external abdominal muscle.

From this vast origin the fibers converge towards the insertion. Those arising from the clavicle pass obliquely downwards and outwards (clavicular portion of the pectoralis major), and are usually separated from the others by a small space. Those of the lower part of the sternum and of the cartilages of the true ribs (abdominal portion of the pectoralis major) run upwards and outwards. The central fibers (sterno-costal portion of the pectoralis major) pass horizontally. All three portions end in a flat tendon, about 5 cm wide, which inserts into the inter-tuberculous sulcus of the humerus.

Note: there are some morphological variations affecting the pectoralis major. The most common are greater or lesser extension of attachment to the ribs and sternum, variable dimensions of the abdominal part or even its absence, greater or lesser extension of the separation between the central and clavicular portion, fusion of the clavicular part with the anterior deltoid and decussation of the part front of the sternum.

Motor functions of the pectorals

The motor functions of the pectorals are mainly dedicated to shoulder movements, more precisely: flexion (movement from top to bottom, frontally), adduction (movement from side to front) and internal rotation of the humerus (as in the arm wrestling) .

- The clavicular part is close to the deltoid muscle and contributes to flexion (up to the horizontal position), adduction in the transverse plane and internal rotation of the humerus

- The sterno-costal and abdominal parts are antagonists of the clavicular part and contribute to downward and forward movement of the arm and inward rotation, if accompanied by adduction. The sternal fibers may also contribute to extension, but not beyond the anatomical position.

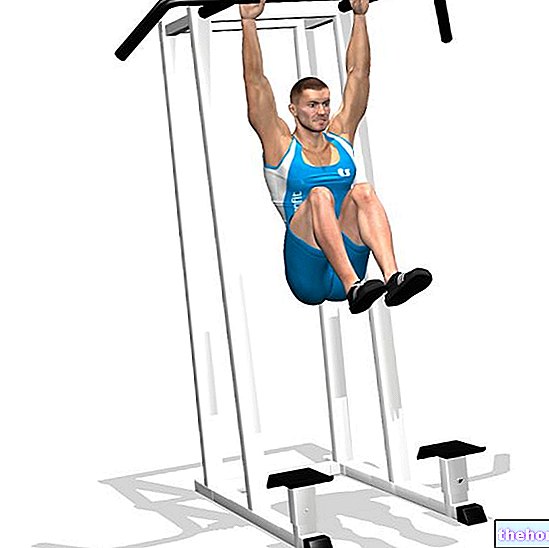

The maximum activation of this muscle occurs on the transverse plane through pressing / distension movements (press). Both multi-joint and single-joint exercises of "isolation" contribute to the hypertrophic growth of the pectoralis major, which however occurs in a "total" manner. only with the simultaneous presence of both.

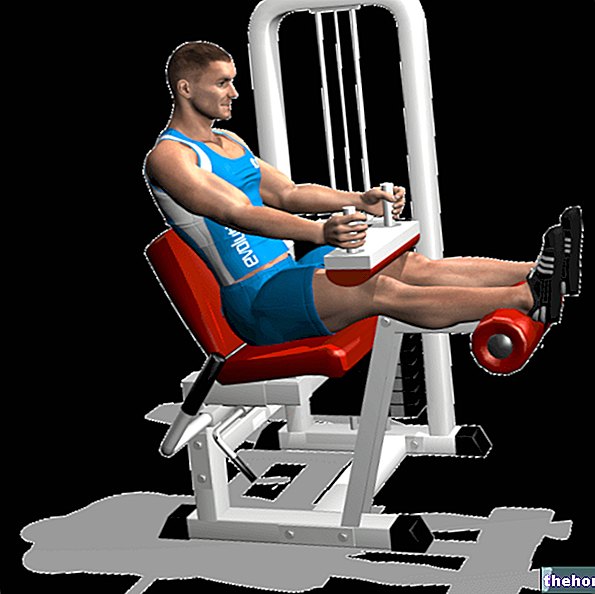

The pectorals can be trained with numerous angles between the humerus and the sternum, and between the humerus and the collarbone. Exercises that include horizontal adduction and elbow extensions, such as bench press with barbell or dumbbells or cables, peck deck, pectoral machine, etc. induce a "high activation of the sterno-costal region. To stimulate the abdominal portion it is necessary that the same movements, with a greater downward inclination; similar speech should be made for the clavicular portion, which requires an "upward inclination".