See also: Esophagitis Barrett's esophagus

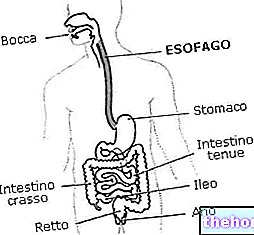

The esophagus is the section of the alimentary canal that joins the pharynx with the pit of the stomach. This muscular duct extends between the sixth cervical vertebra and the tenth thoracic vertebra, for a total length of 23-26 centimeters; its thickness, in the point of greatest diameter, reaches 25 - 30 millimeters, while in the narrowest one it measures 19.

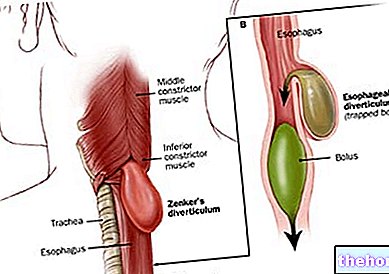

During its course, the esophagus draws relationships with numerous anatomical structures, including the trachea, the thyroid lobes and the heart, anteriorly, the vertebral column posteriorly, and the diaphragm, which crosses at a small opening called the

The esophagus is comparable to a connection tube - with an almost vertical course similar to an elongated S - which allows the descent of food from the mouth to the stomach (antegrade transport) and vice versa (via retrograde during belching and vomiting).

The functions of the esophagus, however, are not limited to simple transport; for example, the lubricating activity is very important, which allows it to keep its internal walls moist, facilitating the descent of food. Furthermore, the esophagus, thanks to the presence of a sphincter for each extremity, opposes the entry of air into the stomach during breathing and the ascent of the gastric contents into the oral cavity.

The passage of the alimentary bolus from the pharynx to the esophagus is regulated by the upper esophageal sphincter.

The passage of the food bolus from the esophagus to the stomach is regulated by the lower esophageal sphincter.

A sphincter is a muscular ring endowed with such an accentuated tone as to remain in a state of continuous contraction; this state can be modified by voluntary mechanism (external anal sphincter) or reflex (like the two sphincters of the esophagus).

The upper esophageal sphincter participates in the swallowing function, opening to allow the pharynx to push the bolus into the esophagus; in resting conditions the musculature that constitutes it is contracted and the sphincter remains closed, preventing the passage of air in the digestive tract and inhalation of food in the airway.

As mentioned, the esophagus has a muscular wall consisting of two structures: an external longitudinal muscle layer and an internal circular one. The propulsive activity is entrusted to the latter, which allows it to perform very important peristalsis movements. a segment of muscles upstream contracts, the downstream stretch relaxes, then this will contract and so on, with succession from top to bottom until the complete descent of the food bolus into the stomach. Esophageal peristalsis is facilitated by the lubricating action of saliva and esophageal secretions.

When the peristaltic wave hits the lower part of the esophagus, a relaxation of the lower sphincter (called cardia) is produced with consequent entry of the bolus into the gastric sac. At the end of this phase, the cardia regains normal hypertonus and prevents the gastric contents from rising into the esophagus. If the lower esophageal sphincter does not have sufficient tone, the gastric juices and pepsin can rise from the stomach causing the so-called gastroesophageal reflux. of a rather common and annoying disorder, since these substances strongly irritate the esophageal mucosa, triggering pain and heartburn (burning sensation).

The internal walls of the esophagus are covered by the mossy cassock, a thick multilayered epithelium that protects it from the transit of food (which may have pointed ends or particularly hard residues). Within certain limits, this effective barrier also protects it from physiological acid reflux. which appears, especially after meals, in all people.

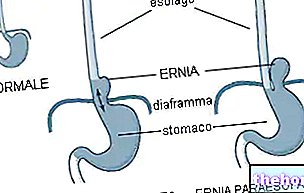

When the cardia, which is normally found below the diaphragm, enters the esophageal hiatus going back up into the thoracic cavity, we speak of a sliding hiatal hernia, a continuously increasing disease especially in people over 45-50 years of age; its symptoms are similar to, but generally more severe, than those of gastroesophageal reflux.