In the previous episode we talked about gastric ulcer and among the main causes that can favor its onset, we mentioned the bacterium Helicobacter pylori. It is a particular microorganism, since it has the exclusive ability to proliferate in the very acidic environment of the stomach, causing, over time, problems such as gastritis, ulcers and inflammation of the stomach and duodenum walls.

L'Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative bacterium, responsible for a chronic infection of the innermost lining of the stomach, called the gastric mucosa. As the term "Helicobacter" recalls, the bacterium has a characteristic spiral conformation. The term "pylori", on the other hand, recalls its preferred site of infection: the pylorus, that is, the point of passage from the stomach to the intestine. L'Helicobacter pylori it is a few microns long and has flagella, that is, structures similar to small tails, which allow it to move and nest in the gastric mucosa. Here it is able to trigger a slow but progressive inflammation that damages the cells of the inner lining of the stomach. Not surprisingly, there is a close connection between the presence of this bacterium in the stomach and the development of gastritis, a chronic inflammation of the gastric mucosa. Infection with Helicobacter pylori it is also considered the main causative factor of gastric and duodenal ulcers, which are real erosions of the stomach wall and the first part of the intestine, called the duodenum. In some cases, theHelicobacter pylori it can even predispose to the development of some stomach cancers.

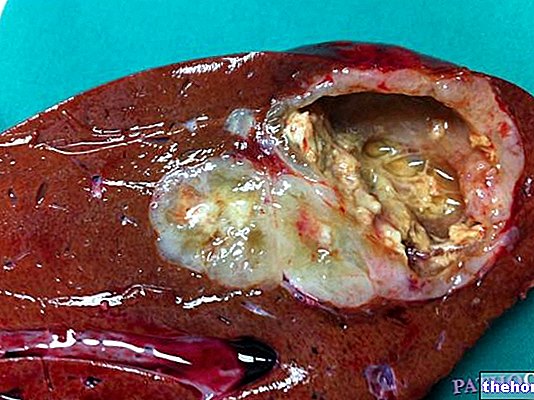

L'Helicobacter pylori it is an unusual bacterium in that it can survive in the very acidic environment of the stomach. This peculiarity is made possible by a stratagem that allows the microorganism to escape the destructive action of gastric juices. L'Helicobacter pylori, in fact, it produces an enzyme, called urease, which allows it to penetrate the mucous membrane of the stomach, where it can also escape the host's immune response. The same enzyme transforms the urea found in the stomach into carbonic acid and ammonia, which partially neutralize gastric acidity.Helicobacter pylori manages to create a microenvironment suitable for its settlement and favorable to its reproduction. Unfortunately, however, in the course of life the bacterium produces substances that have a damaging effect on the gastric mucosa, thus promoting inflammation, called gastritis, and erosion, called ulcer.

As for the contagion, the ways in which theHelicobacter pylori it is transmitted are not yet clear. Probably, transmission occurs from person to person, through direct oral, fecal-oral or through breast milk. Another possible route of contagion is the ingestion of water or food contaminated with fecal material or handled with unwashed hands.

There are no specific symptoms related to the infection. However, the presence ofHelicobacter pylori it can cause annoying digestive problems, with disorders that coincide with those caused by chronic gastritis or ulcer. Therefore, heartburn and stomach pains, gastroesophageal reflux, nausea, vomiting, a sense of heaviness, slow and difficult digestion can occur. However, it should be noted that, in other cases, the infection remains completely asymptomatic; just think that, in the world, two out of three people host the bacterium in their stomach. Many of these people live with theHelicobacter pylori without developing any disease.

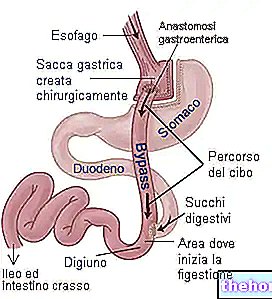

In the presence of gastro-intestinal disorders, even vague ones such as frequent heartburn or digestive problems, it is worth undergoing some simple and accurate medical tests; among these, there are also tests that can demonstrate the presence of the infection. This is the case of the breath test, the search for antibodies againstHelicobacter pylori in the blood and the search forHelicobacter pylori on stool samples. The breath test, also called the Urea breath test, is so called because it measures the amount of marked carbon dioxide emitted with the breath. During the examination, the patient is asked to take marked urea, which is a substance that contains radioactively marked carbon atoms. At this point, if present, theHelicobacter pylori transforms the ingested urea molecule into two smaller molecules: ammonia and carbon dioxide. The labeled carbon thus ends up in the carbon dioxide molecules that are emitted with the breath. If from the analysis of the exhaled air there are high residues of marked carbon dioxide it means that the bacterium lurks in the stomach and the test is considered positive. Otherwise, the infection has not been contracted. To obtain a definitive diagnosis and study the consequences of the infection, a much more invasive examination than the previous ones is required, called esophagus-gastro-duodenal-scopy. This endoscopic examination is carried out by introducing an optical fiber tube through the mouth, then gently lowered to allow observation of the mucosa of the esophagus, stomach and duodenum. At the same time, the investigation allows to perform a biopsy, that is to take small fragments of tissue which will then be analyzed under a microscope to assess the damage caused by the bacterium to the gastric and duodenal mucosa. The biopsy sample can also be cultured to identify the bacterium and antibiotics to which it is most sensitive.

Once the presence of theHelicobacter pylori, the therapy to fight the infection is essentially antibiotic. The treatment involves taking one or two different types of antibiotic for 7-14 days, chosen from amoxicillin, metronidazole, clarithromycin and tetracycline. This basic antibiotic therapy is then associated with a drug that reduces stomach acid secretion, such as proton pump inhibitors. These powerful antacids relieve symptoms and create a less favorable environment in the stomach for the bacterium to live. When followed according to the precise medical indications, this combined therapy is decisive in about 90% of cases. Once theHelicobacter pylorimoreover, the problems associated with its presence also significantly improve.

Since we still know little about the methods of transmission of theHelicobacter pylori, even the preventive measures are not well defined. In general, however, it is recommended to always wash your hands thoroughly before touching or eating food. In addition, it is possible to act by limiting other important factors that can predispose to gastro-intestinal problems, such as alcohol abuse, smoking and chronic non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as aspirin.