Statistics from the Divers Alert Network (DAN) [2] and the University of Rhode Island [3] argue that panic was responsible for 20-30 percent of fatal diving accidents and is probably the leading cause of death in diving activities.

But what exactly happens in the diver's mind?

.eidner [4] points out that the early stages of many forms of stress can be associated with "anxiety and points out that the fear of having an accident" is part of the latter.

This fear can be real or symbolic. According to Zeidner, the main characteristics of this type of anxiety are:

- The individual perceives their situation as threatening, difficult or challenging;

- The individual considers his ability to cope with this situation as insufficient;

- The individual focuses on the negative consequences that will follow from their failure (to solve problems), rather than focusing on finding possible solutions to their difficulties.

Persistent anxiety over a long period of time can escalate into a state of panic.

Anxiety, however, always refers to an excessive sense of apprehension and fear. Let's look at it in more detail.

than psychological.Anxiety can lead to doubts about the nature and reality of the threat as well as self-related doubts about coping with the situation.

Physical symptoms can vary widely, from sweating of the hands and tachycardia of the medium forms to psychomotor agitation, emotional paralysis or the triggering of a panic attack or phobic reaction. The difference is only a technical fact.

The symptoms of anxiety vary from person to person, from one situation to another and even from one moment to another in the same subject.

Anxiety serves a very specific purpose: it is an alarm to a threat, which has a survival value.

Escape is the most typical behavioral response to fear.

Occasionally, however, "direct action (fighting instead of running away) is required, and" physiological activation can sometimes provoke a hero reaction, such as attacking a shark or jumping into the cold waters of a river to save a drowning dog.

Some studies have shown that an average level of anxiety guarantees optimal performance in certain situations.

People who experience mild to moderate degrees of anxiety have a degree of "arousal" which allows them to perform better than people who do not experience anxiety.

An average level sometimes causes an increase in motivation to focus on one's goals.

An excess, on the other hand, tends to make the individual focus on himself and on his own fears, distancing him from his objectives.

A low level of anxiety can help the diver be more cautious.

An excessive state of anxiety can lead to that reduced cognitive and perceptive dimension, in which the diver's concentration and attention can shift to inner fears making him neglect important aspects, such as the slow ascent to the surface.

However, anxiety and panic are two quite different conditions.

and panic symptoms are more pronounced.The panic attack has a sudden onset, reaches a symptom peak very quickly (10 minutes or less from onset), subsides within 60 minutes, and is often accompanied by a sense of impending doom and an urge to get away.

The symptomatology of panic is much more debilitating than the anxiety crisis; rational thinking is suspended and people can get stuck, for example they remain fixed in one position or react in an unpredictable way or in a way that puts themselves in danger [5].

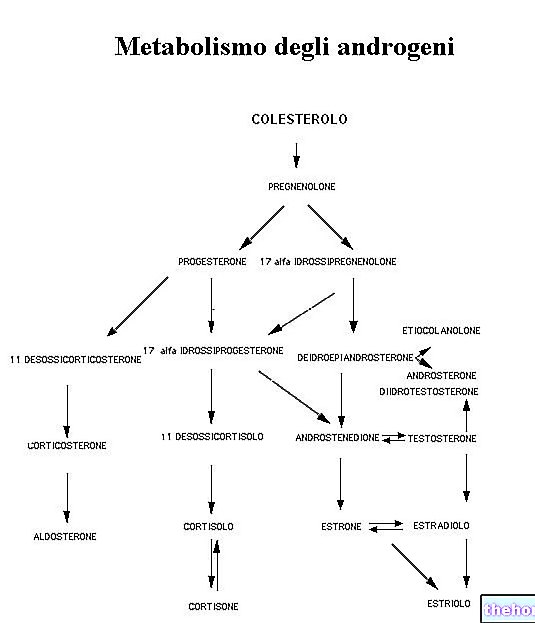

, arterial pressure, accelerated breathing, etc.) which express a modification of the activity of the Autonomous Nervous System and in particular of its adrenergic component.

This might suggest that there are objective parameters by which to measure the severity of the anxiety disorder and its variations.

In reality, anxious feelings (and therefore the severity of the disorder) correlate poorly with physiological parameters, both due to a "high subjective variability of the physiological response to stress, and because the correlation between physiological activity and somatic sensations is low."

Ultimately, therefore, the modifications of the physiological parameters in relation to the anxiety disorder have a considerable heuristic interest, but they are almost unusable in the evaluation of the severity and modifications of the psychic component of this disorder because there is no two-way relationship between them.

Professional divers and those who have taken rescue courses are trained to recognize symptoms of anxiety in themselves and in others [6], which can be summarized in the following attitudes:

- Accelerated breathing or hyperventilation

- Muscle tension;

- Joints blocked

- Eyes wide open or avoidance of eye contact;

- Irritability or distractibility;

- "Escape to surface" behavior;

- Tempting, for example spending too much time preparing equipment or entering the water;

- Imaginary problems related to equipment or ears;

- Being talkative or becoming detached and silent

- Maintain a tight grip in the water with the boat ladder or anchor line.

It is essential that instructors learn to intervene before the mood or stressful events become excessive, leading to exhaustion, panic or a diving accident.

If anxiety and panic triggering symptoms increase, the diver's ability to identify them and find an adequate response decreases.

In a challenging situation it is very difficult for the diver to recognize and stop the escalation of anxiety before it reaches panic proportions.

Even the behavior of the subject (going up quickly to get out of the water, irritability, contemptuous attitude of danger, continuously emitting bubbles, etc.), like the physiological parameters, is extremely variable from individual to individual and does not closely correlate with the subjective feeling of anxiety: for this reason it cannot be taken alone as a reference point for identifying and measuring anxiety.

The primary source of information therefore remains what the subject reports, the other two fields (physiological and behavioral aspects) being able to contribute only to underline, confirm or amplify what is communicated.

A diver may appear calm and have no changes in breathing and heart rate, but present a panic attack shortly after.

It follows therefore that for the evaluation of anxiety disorder it is necessary to use standardized evaluation tools such as self or heterosadministration tests and questionnaires..

which can accompany panic on land.Panic attacks, according to the DSM-IV-TR [9], can occur in the context of any anxiety disorder as well as in other mental disorders (social phobia, specific phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder or separation anxiety disorder) and some general medical conditions.

They are divided into:

- Unexpected (unprovoked) panic attacks: the diver has no stress factor and feels the "clear sky" attack;

- Situational panic attacks (provoked) that occur immediately after exposure to, or waiting for, a stimulus or situational trigger, such as air loss or other equipment malfunctions, disorientation in a wreck or in a cave, very poor visibility or not seeing the diving buddy anymore;

- Situation-sensitive panic attacks, which are similar to the attacks in point b, but are not invariably associated with the stimulus and do not necessarily occur immediately after exposure (for example, a panic attack occurs after half an hour of crossed a shark or after having made a descent into the "blue" away from the wall).

It has been observed that anxious individuals, subjected to strenuous exercise while wearing a mask, tear it off their face if they believe they cannot breathe properly.

It was reported that panicked divers took off their regulators and resisted if their buddy tried to put it back in their mouth, despite having full tanks and a fully functional dispensing system.

A simple thought or association can often trigger a chain reaction of thoughts, such as the following:

'I have too much weight - What if I sink too fast? - I could break an eardrum - No one might be able to reach me in time - I could end up on the bottom more than 25 meters away from the reef - I could be injured - I am about to drown - Panic!'.

One question remains: why some people experience a panic attack, while others show only anxiety and manage the situation rationally?

The factors can be different, including:

- the specific importance of the external stimulus for the individual involved;

- the fact that there has been specific training;

- the results that the training has had in strengthening the defenses and the adaptability of the individual towards unforeseen situations.

However, the suggestions proposed by these five studies are not supported by significant empirical evidence. A methodological proposal, which I believe is easy to apply and can represent a simple method for the prevention of diving accidents due to panic attacks during diving, is based on the opportunity to recognize the individuals most susceptible to panic by suggesting a small battery test:

- Thyer's Clinical Anxiety Scale (CAS), a 25-item self-assessment scale that aims to measure the quantity, degree and severity of anxiety. The CAS, formulated in simple language, is easy to administer and interpret. and has proved capable of discriminating between anxious and non-anxious subjects [15].

- The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), developed by Spielberger, is one of the most used tests to identify the possible predisposition to anxiety and panic and differentiates anxiety into state anxiety and trait anxiety [16].

- Self-rating Anxiety Scale (S.A.S.) by Zung, which allows to evaluate anxiety as a clinical entity through the objective measurement of information coming only from the subject [17].

CAS is a screening test, people who report a significant anxiety score are evaluated with the STAI to identify anxiety as a personality trait.

The Zung scale should be a kind of reminder that the diver goes through in order to train himself to quantify his level of anxiety.

It is clear that individuals who score high on anxiety traits potentially have a higher risk of developing a panic attack than those who score normal.

These tests can identify a panic tendency with very high accuracy.

The predisposition to anxiety can, however, be overcome with the help of experience and training.

Therefore, excluding those who simply have a higher intrinsic level of anxiety from diving would be difficult and probably not legitimate.

One has to ask, however, whether the topic of panic diving is sufficiently addressed as the risks associated with panic could be underestimated as a result of the need to promote and "commercialize" diving.

It is therefore essential that the didactics devote ample space to the problem of the anxious diver, panic and its management, right from the first levels of training and, in particular, during the training of instructors.

, mitral valve prolapse, cardiac arrhythmias, vestibular dysfunction, premenstrual syndrome, some symptoms of menopause, diabetes, hypoglycemia, thyroid and parathyroid disorders, asthma and some systemic infections.

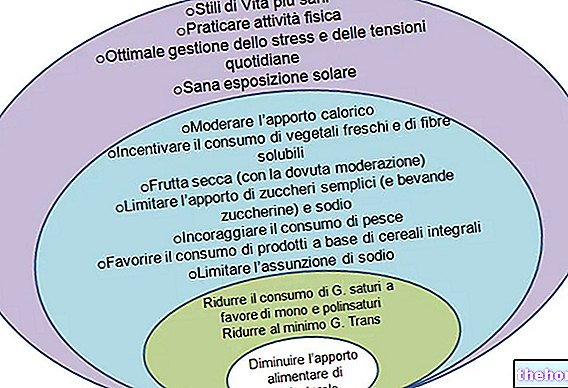

Numerous medications can aggravate a state of anxiety.

Some substances such as caffeine, nicotine and other products used as stimulants, pseudoephedrine (a decongestant) [18], theophylline (a bronchodilator used in the treatment of asthma or chronic bronchitis), some antihypertensive drugs and alcohol withdrawal can precipitate a panic attack. Similarly, concomitant psychological stresses, such as work problems, economic worries, relationship difficulties, previous experiences or thoughts of a devaluing nature (such as doubting one's abilities or feeling that you are not in control of the situation) can increase the chances of onset of panic.

Some research has found that chronic worries predispose more to anxiety reactions and involve greater difficulty in the ability to relax than individuals who are less prone to worry or obsessive ruminations [19].

Numerous researches discuss the use of drugs for the prevention of panic attack and many subjects who practice scuba diving have been prescribed drugs, such as imipramine, propanolol, paroxetine, fluoxetine or alprazolam, which are used in the therapy of the disorder. "anxiety and panic attacks.

These same studies acknowledge some concerns about divers' use of certain medications, especially if they have a tendency to make them sleepy or because they could in any way harm the diver's awareness of the environment [20].

A variety of non-pharmacological techniques for the treatment of anxiety have also been used, for which there are few contraindications and in some people, such as those who have side effects to drugs, may be preferable.

The main ones are:

- systematic desensitization,

- implosive techniques,

- the cognitive-behavioral technique;

- hypnosis.

Understanding the mechanisms of anxiety helps you understand how these techniques can work.

, such as breath control and alternating tension and relaxation of muscle groups to arrive at an awareness of the difference between being tense and being relaxed.The student develops a hierarchy of thoughts and behaviors that produce anxiety, ranging from those that produce the least state of anxiety (standing on the edge of the pool) to those that produce a greater one (being in the pool with complete equipment) up to those who give the maximum of anxiety (being immersed in the bottom of the pool).

People can go through a series of mental exercises, such as imagining approaching the water, preparing their equipment carefully and meticulously, then going down to the pool.

Some subjects, on the other hand, may choose to perform a series of exercises, such as walking in the pool, breathing through a regulator while standing in the water that reaches their belt, kneeling with their head only underwater.

A combination of the two methods can also be performed.

Based on the individual motivations of the students, the patience of the instructors, the dive masters and the dive buddy, the diving candidate should be able to significantly reduce his anxiety to the point of experiencing the pleasure of diving.

As a result of this, any dive that has been successfully conducted tends to reinforce the positive aspects of recreational diving.

. When an intrusive and troubling thought begins, the pupil can snap the rubber band against his wrist.

This stinging and slightly painful sensation immediately draws the attention that had been taken in an anxiety-producing thought.

At that moment, then, the diver says to himself "Stop". With time and a little practice, these techniques achieve remarkable results in reducing anxiety.

about 15 meters deep.When he tries to fin harder to free himself he finds himself wedged deeper.

He has an anxious reaction "I'm stranded. What" happened? I can't get away from here! Oh my God! I got tangled up in this stuff! ".

After every attempt to free himself, Carlo finds himself more blocked. It begins to hyperventilate and quickly consumes the air.

He is not sure if the algae have become entangled in his body or on the tank.

At one point he decides to take off the BCD and the cylinder and makes an emergency ascent risking drowning.

The onset of the panic attack must involve, instead, the following sequence:

- STOP: "I got entangled in the algae. I feel like I can't move. I stop and imagine how to get out of it."

- BREATHE: "I need to control my breathing. I take slow, deep breaths while thinking about this. I should still have 100 bar of air to breathe in the tank."

- THINK: "Since I can't move, I have two options: try with the knife to cut what is blocking me or try to take off my jacket and tank".

- ACT: Carlo slides his right hand down the leg and takes the knife. Slowly and carefully he begins to cut at the height of the belt all the algae he can see or hear. By making slight rotational movements he continues to cut wider and wider areas. In a few minutes he can turn completely and cut the remaining algae around the Here he puts the knife away and begins a slow ascent to the surface.

Example 2

Alberto, at a depth of 18 meters, realizes that he has run out of air.

He can't see his dive buddy. He has a panic attack: "Oh my God, I'm going to have to die! How could that happen? I can not breathe! Where the hell is my mate? He left me here. "

Alberto sees the distant surface and begins to fin as hard as he can upwards.

In a panic and without thinking, he holds his breath and reaching the surface is struck by Decompression Sickness (DCS). Again, the cognitive sequence should have been the following.

- STOP: "I have run out of my air supply, for sure." I can't see my partner and I don't have time to look for him. "

- BREATHE: "That's the problem. I can't inhale water."

- THINK: "I'll have a good half minute of air in my lungs." I have to remember the first rule of "scuba diving" "Never hold your breath". D "okay, I have to do an emergency ascent. I must be sure to exhale fully on ascending. It is better than releasing and releasing the weight belt."

- ACT: Alberto removes the belt which quickly falls down. He uses the whip to inflate the BCD a little and find that there is enough air left for this purpose. He swims quickly to the surface while continuing to exhale and does all this by focusing on the air bubbles coming from his lungs. In a few seconds he reaches the surface and at that moment manually inflates his BCD.

Alberto was saved because he reacted appropriately to an extremely distressing situation.

Example 3

Giovanna, a scuba diver who has recently completed her certification, books herself to go one morning for a wreck dive with a group of experienced divers.

She is alone and believes that she will be able to find a partner on the boat.

Sufficiently safe she is paired with some sort of diving Rambo, who has already done hundreds of dives in that area.

Arriving close to the wreck site, the guide informs the group that the first dive will be made at 30 meters, more than double the maximum depth that Giovanna has ever reached before. Almost panic.

Giovanna is anxious: "I can't retire now".

He rationalizes: "This dive should be no different from the two previous ones I did at 60 feet during the certification course.

Scared, she thinks: "What will happen if I lose contact with my partner? Will I have to follow him into the wreck? Will I be able to wait for him? Will I finally have enough air? Damn, how do I decide? If I say something I'll be taken for a" goose. !

I have to dive in and see what happens. But what do I do if a problem arises? Prey to doubts, anguished and hyperventilating, Giovanna begins the dive.

A few minutes later, while she is swimming above the wreck and tries to stay close to her partner, Giovanna is shocked to see that the pressure gauge signals that she is about to enter the air reserve area: she then interrupts the dive and climbs quickly without carrying out the safety stop. Giovanna should have:

- STOP: "The first dive to 30 meters? This is not a situation that guarantees my safety based on my level of preparation".

- BREATHING: "I don't need to experience a panic attack. I'm glad I didn't dive. My breathing returns to normal and so are my sensations."

- THINK: "I've never been to that depth and now is not the time to go, especially with Rambo as a dive buddy. I don't have much hope that he will be near me. I went into trouble just thinking about all the worst things that could happen to me down there. "

- ACT: Giovanna tells the Dive Master that she has recently obtained her certification and that she does not feel safe to carry out this dive at 30 meters and that she prefers not to dive and instead participate in the second one which will take place in the late morning around 18 meters with everything the group of divers. "There is no problem" replies the instructor. Rambo will pair up with another person and Giovanna will make the safest dive a couple of hours later.

The purpose of this cognitive "strategy" is to always remember and repeat frequently, that in the event of an emergency "any problem can - and should - be solved underwater" and not through an uncontrolled ascent.

Considerations

In the main scuba diving teaching manuals in reference to stress you can find phrases such as: "If you don't feel right, always remember to Stop, Rest, Think and, only then, Act.

If you go towards the surface, you need to do it slowly and in a controlled way, breathing regularly and paying particular attention to the exhalation.

Once on the surface, inflate the BCD well and release the weight. In emergency situations, buoyancy will be better and getting back into the boat easier.

If you know that you have a tendency to panic, avoid immersing yourself in potentially stressful situations or with partners you do not know well and who may not help you cope effectively with a situation of sudden anxiety.

Whatever happens, think and fight the panic. "

The limit of these suggestions is related to the fact that it can find validity only with regard to panic attacks that the DSM-IV-TR classifies as "caused by the situation (provoked), while it has no relevance for the other two forms of panic, those unexpected and sensitive to the situation, which clinically represent the majority of panic situations.

Another striking element of the manuals on diving is the terminological confusion between stress, anxiety and panic and the "absence of argumentation on" arousal "in the part of the didactics dedicated to accidents in diving.

in divers exposed to various stressors, but they were not always effective. Some research has shown, for example, that hypnosis can achieve relaxation in the diver, but that it can have undesirable effects such as a lack of energy.

Relaxation can lead to increased anxiety and panic attacks in overcontrolled or very anxious individuals (this phenomenon is known as "Relaxation-indiced-anxiety" RIA).

Individuals with a history of anxiety and panic disorder should be identified and undergo specific training that reduces the potential risk of a flare-up of the disorder. The problem is that people who join this recreational activity, which is becoming more and more popular, they do not know the risks and dangers it can entail.

It is essential that those who practice diving can be able to have an internal dialogue about their feelings of anxiety in a given situation. Expectations, negative fantasies, worries, are all aspects that can be misleading by making a situation experience more negative than what it should be and usually even before the situation itself is encountered.

to the situation.The person recognizes that the fear is excessive or unreasonable and avoids the situation or endures it with intense anxiety and discomfort.

There are various subtypes of specific phobia; those that may occur during the course of an underwater activity can be classified as follows:

Type Animals

This subtype refers to the fear of fish (Ittophobia) or, more specifically, of sharks or Elasmophobia. The latter is related to Phagophobia or the fear of being eaten alive. This subtype generally has its onset in childhood.

Natural Environment Type

It includes Thalassophobia, which is an irrational fear of the sea, Hydrophobia or fear of water (which usually begins in childhood), Batophobia or fear of depth or diving to the bottom in case of deep diving and Nictophobia or fear of darkness in case of night dives.

Situational Type

It includes Claustrophobia (fear of being closed or stuck) which can manifest itself in wreck diving or underwater caving, Barophobia (fear of being crushed) triggered by the idea that the mass of water above can crush the diver.

Other type

Some stimuli can trigger other phobias such as Thanatophobia (fear of dying) or Pnigophobia, which is the fear of not being able to breathe or suffocating. In the clinical setting, the most frequent subtype is the Situational one, followed by the fear of animals (sharks, in the case of those who dive).

See other articles tag Underwater - Apnea

-nelle-carni-di-maiale.jpg)