Generality

The term retinitis pigmentosa (RP) identifies a group of genetic diseases characterized by progressive retinal degeneration.

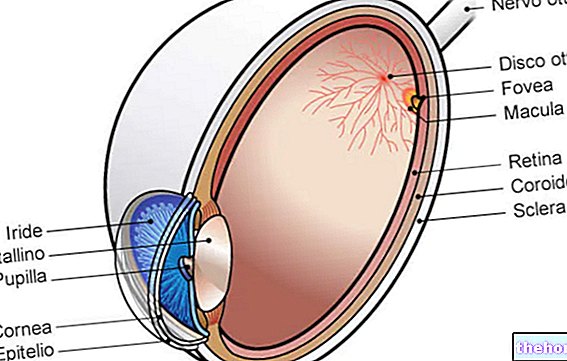

Retinitis pigmentosa is a retinal dystrophy characterized by the gradual loss of photoreceptors and dysfunction of the pigment epithelium. This means that the retina progressively reduces its ability to transmit visual information to the brain via the optic nerve.

The pathological process begins with alterations of the retinal pigment epithelium. As retinitis pigmentosa progresses, there is a thinning of the blood vessels that supply the retina, which undergo atrophy. Upon examination of the fundus, the characteristic deposits are visually detectable. retinal pigment (hence the name from the disease). Atrophic changes and damage can also involve the optic nerve and, gradually, the photosensitive cells of the retina die.

Patients affected by retinitis pigmentosa initially experience vision problems especially in low light environments and complain of a constriction of the peripheral visual field. Central vision is spared until the later stages of the disease, and the final outcome can vary dramatically: many people with retinitis pigmentosa retain limited vision throughout their lives, while others lose sight entirely.

Retinitis pigmentosa is an inherited disease, mainly caused by genetic changes passed on from one or both parents. The type of genetic defect determines which retinal cells are most involved in the disorder and makes it possible to distinguish, from a clinical point of view, the different conditions. To date, more than 50 different genetic defects implicated in retinitis pigmentosa have been identified. Abnormalities can be passed from parents to offspring through one of three inheritance patterns: autosomal recessive, autosomal dominant, or heterosomal recessive (X-linked or X-linked).

Symptoms

For further information: Retinitis Pigmentosa Symptoms

Retinitis pigmentosa is usually found in adolescents and young adults. Symptoms often appear between the ages of 10 and 30, but the diagnosis can be made in early childhood or much later in life.

Early symptoms of retinitis pigmentosa can include:

- Difficulty seeing at night (night blindness) or in low light conditions

- Slow adaptation from vision in the dark to that in light, and vice versa;

- Narrowing of the visual field and loss of peripheral vision;

- Sensitivity to light and glare.

Some symptoms depend on the type of photoreceptors involved. The rods are responsible for black and white vision, while the cones allow you to distinguish colors.

In most cases of retinitis pigmentosa, the rods are involved first. However, in the rapidly evolving forms, cones can also be affected at an early stage.

Rods are concentrated in the outer parts of the retina and are activated by dim light, so their degeneration affects peripheral and night vision. If cones are involved, it is possible to experience loss of color perception and central vision.

The predominance of photoreceptors involved is determined by the particular defect present in the patient's genetic makeup.

Often, the first symptom of retinitis pigmentosa is night blindness (or nocthalopia). Some people find that they need more and more time to adjust to differences in light as they move from a well-lit area to a darker one. A typical form of vision loss induces narrowing of peripheral vision (tunnel or telescope vision); this pattern is called a ring scotoma. Sometimes, this phenomenon may be missing in the early stages, but it is noticed when the individual often trips over objects or is involved in a traffic accident. When vision loss involves the central area of the retina (also called macular dystrophy) patients experience difficulty with reading and detailed work that requires concentration on a single object, such as threading a thread through the eye of a needle Many patients report seeing flashes of light (photopsia), often described as small, flickering and twinkling lights.

The rate of disease progression and the degree of visual loss vary from person to person. Some extreme cases may evolve rapidly within two decades, others a slow course that never leads to complete blindness. Early onset is found in more severe forms of retinitis pigmentosa, while patients with milder conditions (eg, autosomal dominant) may develop the disease in their fifth or sixth decade of life. In families with X-linked retinitis pigmentosa, men are affected more often than women and more severely; females, on the other hand, transmit the genetic characteristic (they carry the altered gene on the X chromosome) and manifest symptoms of the disorder less frequently.

Complications

Retinitis pigmentosa will continue to progress, albeit slowly. However, complete blindness is rare, but significant reduction in peripheral and central vision can occur.

Patients with retinitis pigmentosa often develop swelling of the retina (macular edema) or cataracts at an early age. These complications can be treated if they interfere with vision.

Related diseases

Commonly, a patient with retinitis pigmentosa has no other disorders and in this case we speak of "non-syndromic" or simple retinitis pigmentosa. However, several syndromes share some clinical symptoms with this eye disease; the most common is Usher syndrome, which affects approximately 10-30% of all patients with retinitis pigmentosa and is associated with concurrent congenital or progressive hearing loss. In Leber's congenital amaurosis, however, children can go blind, or nearly blind, within the first six months of life. Other diseases related to retinitis pigmentosa include Bardet-Biedl syndrome and Refsum disease.

Causes

The disease can be caused by a number of genetic defects: in fact, there are several genes that, if affected by the alteration, can cause the retinitis pigmentosa phenotype. These normally encode proteins involved in the transduction cascade that allows vision, factors cell transcription (which send erroneous messages to retinal cells) or for elements that make up the structure of photoreceptors. Inherited gene mutations are present in cells from the moment of conception; common abnormalities include those of RP1 genes (in retinitis pigmentosa-1, autosomal dominant), RHO (RP4, autosomal dominant) and RDS (RP7, autosomal dominant). Non-hereditary causes of retinitis pigmentosa are rare, but the possibility of finding an isolated case (spontaneous mutation), in which it is not present a family history of the disease.