What are Metastases?

Metastasis is the spread of a tumor malignant in a different location from that of origin. In fact, some cancer cells, in addition to growing in an uncontrolled way and confusing the body's defensive mechanisms, acquire the ability to detach themselves from the initial neoplastic mass and implant themselves in other organs or tissues.

The spread of a tumor can occur by continuous (local) extension or at a distance, through the bloodstream or the lymphatic system. Generally, the ability to metastasize is a distinctive feature of malignant tumors, which allows them to be distinguished from benign neoplasms. Metastatic spread greatly reduces the possibility of cancer cure, but current treatment options allow to control the growth of the cancer, alleviate the symptoms caused by it and, in some cases, can help prolong the life of the cancer patient.

- Tumor (or neoplasm): clonal expansion of a genetically abnormal cell, which loses control of cell cycle regulation.

- Benign tumor: mass that expands while remaining localized in the site of origin; in some cases, it can become harmful.

- Malignant tumor: cells do not respond to normal control mechanisms, but actively proliferate. It is also called cancer (or carcinoma). The disease, caused by malignant cells, is characterized by overgrowth (high number of cell divisions), metastasis and invasiveness of other tissues and organs.

Features

- A tumor made up of metastatic cells is called "metastatic"; it is made up of the same type of clones that form the original neoplastic mass, of which it also assumes the same name. For example, a breast cancer that spreads to the lung and forms a metastasis is called "metastatic breast cancer" and not "lung cancer".

- In most cases, the presence of metastases indicates the more advanced stages of neoplastic progression. The histological examination is a fundamental tool for obtaining important information on the degree of aggressiveness of the tumor and on its ability to metastasize; the results therefore allow the development of an adequate therapy. In general, the more aggressive the primary cancer is , the more likely it is to metastasize.

- With a few exceptions, all malignant tumors can metastasize (for example, gliomas and basal cell carcinoma rarely metastasize).

- Under the microscope, metastatic tumor cells are identifiable by some typical characteristics of the original tissue and not of the implantation site.

- Furthermore, primary and metastatic tumor cells share some molecular characteristics, such as the expression of certain proteins or the presence of specific chromosomal alterations.

How they are formed

The development of metastases is a complex phenomenon in which numerous factors are involved that affect both the tumor and the host organism.

These variables can include:

- Genetic characteristics of the disease;

- Type of body involved;

- Availability of ways for dissemination.

Not all cancer cells have the ability to metastasize. Furthermore, successfully reaching another area of the organism does not necessarily guarantee the onset of a secondary neoplasm. In order for a tumor to cause the formation of metastases it is in fact necessary that its cells are able to:

- Invade the basement membrane;

- Moving through the extracellular matrix;

- Penetrate and survive in the lymphatic or vascular circulation;

- Get out of circulation and enter a new site;

- Survive and grow as metastases (example: angiogenesis).

Routes of dissemination

Dissemination of metastatic cells can occur:

- Direct implantation: when cancer cells proliferate, they can invade and grow directly into the surrounding tissue; moreover, they can spread by contiguity in a body cavity (as, for example, in the case of the peritoneum, pleural cavity, pericardium or subarachnoid space).

- By lymphatic route: cancer cells infiltrate the lymphatic circulation and are transported to the drainage nodes. The lymph nodes closest to the primary tumor mass (also called "sentinel lymph nodes") may be enlarged due to tumor infiltration and growth or by metaplasia due to the tumor-specific immune response.

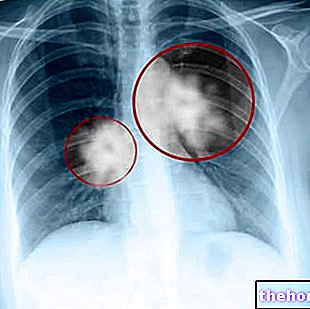

- By blood: the veins are preferentially infiltrated, so the metastases attack the arrival points of the venous circulation, such as the liver or lungs.

Sentinel lymph nodes and tumor metastases

- The lymphatic capillaries offer little resistance to the passage of cancer cells and allow a rapid spread of the tumor.

- In this case, the lymph nodes represent passageways for migrating cancer cells; their clinical examination can provide information on the spread of a carcinoma.

- The degree of colonization of the lymph nodes is a criterion considered in the staging of breast cancer and lymphomas.

Location

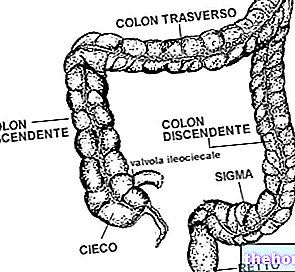

The ability to colonize other organs varies greatly from tumor to tumor. The most common sites of metastases are the liver, lung, bone, and brain, but cancer can spread almost anywhere in the body. Some primary tumors preferentially metastasize to certain parts of the body. This "tropism" depends on the anatomical location, the type of neoplasm and a number of other factors. For example, if a tumor affects the intestine, whose waste blood is drained through the portal, it is clear that the site of the primary metastasis will be the liver. If, on the other hand, the tumor is in a site drained by the vena cava, the metastasis primary will be mainly in the lungs (Vena cava → Heart → Pulmonary artery). There are, however, particular cases in which tumors have preferences independent of anatomical positions: those of the breast and prostate, for example, often cause bone metastases, as it exists a close correlation between these organs and Batson's venous system (connects the pelvic and thoracic veins to the internal vertebral venous plexuses).

Furthermore, there are cells which, due to the type of receptors they express, have a predisposition to colonize some specific tissues.

The following table shows the most common sites of metastases, excluding lymph nodes, for different types of cancer:

Signs and symptoms

Some patients with metastatic tumors show no signs and the condition is often found during follow-up checkups. When they occur, the type and frequency of symptoms depend on the size and location of the metastasis.

- Skeletal involvement can result in bone pain and pathological fractures of the affected bones.

- A tumor that metastasizes to the brain can cause a variety of symptoms, including headaches, dizziness, visual disturbances, seizures, and neurological deficits.

- Lung metastases usually produce very vague manifestations, which can be linked to other problems. These can include cough, hemoptysis, chest pain and shortness of breath.

- Hepatomegaly, nausea, loss of appetite, and jaundice may indicate that a tumor has spread to the liver.

Sometimes, the presentation of symptoms related to a metastasis allows it to be identified before the primary tumor. For example, a patient whose prostate cancer has spread to the bones of the pelvis may have back pain before experiencing symptoms of the original tumor.

Diagnosis

A metastasis always coincides with a primary tumor, and as such is caused by cancer cells from another part of the body. If symptoms of secondary cancer are present, if the result of a follow-up test is abnormal or if the doctor suspects a metastasis, some diagnostic tests are done.

The path may involve:

- Complete physical examination;

- Laboratory tests;

- Imaging: radiographs, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET);

- Biopsy.

In most cases, when a metastasis is found before the primary tumor, investigations are aimed at establishing the origin of the pathological process.

Biopsy

- To determine if a tumor is primary or metastatic, part of the cancerous tissue can be taken and examined under a microscope. The use of sample techniques, such as immunohistochemistry and FISH (fluorescent in situ hybridization), allows pathologists to determine where cancer cells are coming from.

- In some cases, the primary tumor remains unknown.

Tumor markers

Some cancers are characterized by tumor markers. Specific blood tests evaluate their expression and can be useful in monitoring the disease after it has been diagnosed. Increased levels of these markers may indicate that the tumor is active or progressing.

Some examples of tumor markers are:

- Carcinomas of the colon, pancreas, lung, stomach and breast: CEA (carcinoembryonic antigen);

- Ovarian carcinoma: CA-125;

- Prostate cancer: PAP (prostatic acid phosphatase), PSA (prostate specific antigen);

- Multiple myeloma: immunoglobulins;

- Medullary thyroid carcinoma: calcitonin;

- Testicular tumors: AFP (alpha-fetoprotein), HCG (human chorionic gonadotropin).

Diagnostic for images

- Ultrasonography is an excellent tool for identifying a neoplastic mass in the abdomen and allows you to distinguish suspicious liver cysts.

- A computed tomography (CT) scan can be used to scan the head, neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis. CT with contrast is good for detecting masses inside the lymph nodes, lungs, liver, or other structures.

- A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used to define potential damage to the spinal cord, in the presence of bone metastases, or to characterize brain involvement.

- An X-ray can be done to see if a tumor has spread to the lung.

- A bone scan is useful for providing evidence of bone damage and allows you to define whether this is caused by a metastasis.

- In some cancers, a positron emission tomography (PET) scan can detect areas of hypermetabolic activity anywhere in the body and can detect even very small metastases.

Treatment

Patient treatment and prognosis is determined, to a large extent, by whether or not a tumor remains localized to the site of origin. If the tumor metastasizes to other tissues or organs, the probability of survival usually decreases dramatically (i.e. the prognosis becomes poor). Depending on the case, a metastatic tumor can be treated with systemic therapies (chemotherapy, immunotherapy, hormone therapy), local interventions (surgery and radiotherapy), or a combination of these options ("multimodal therapy").

The treatments chosen to treat a metastatic tumor depend on many factors, including:

- Primary tumor type;

- Location, size and number of metastatic tumors;

- Patient's age and general health condition;

- Previous therapeutic modalities to which the cancer patient has been subjected.

The treatment options available are rarely able to cure metastatic cancer and are often aimed at keeping the disease under control or reducing its symptoms. Management of metastases is difficult, as cells that survived the first therapeutic approach could develop resistance to chemotherapy drugs or radiotherapy treatments. It is important to remember that metastases almost always cause the patient's death; only in rare cases is the primary tumor directly responsible. For this reason, it is important that the diagnosis is made as early as possible (usefulness of screening tests in subjects at risk)