Definition

Always unpredictable, the spontaneous variant of pneumothorax is probably the most common form, affecting mostly young, slender, long-limbed males.

Responsible for even major respiratory difficulties, spontaneous pneumothorax outlines a complex clinical picture, consisting in the accumulation of air or gas in the pleural cavity and the consequent collapse of the lung.

Pleural cavity: connecting element between the lung and the chest wall.

Classification

Spontaneous pneumothorax is divided into several sub-categories:

- NEOATAL SPONTANEOUS PNEUMOTHORAX: Infants with severe lung diseases such as SAM (meconium aspiration syndrome) and RDS (respiratory distress syndrome) can develop complications such as spontaneous pneumothorax. Most newborns with spontaneous pneumothorax do not complain of symptoms: this constitutes a serious limitation for an early diagnosis. In other infants, however, the disease begins with evident prodrome, such as cyanosis, hypoxia, hypercapnia and bradycardia.

- PRIMARY OR PRIMITIVE SPONTANEOUS PNEUMOTHORAX: occurs in the absence of an apparent cause or lung disease. Most of the affected patients recover spontaneously in 7-10 days from the onset, without reporting damage in the long term. The pathogenesis is generally linked to the breakdown of the so-called blebs, accumulations of air undermined between the lung and visceral pleura. It is estimated that the primitive spontaneous variant constitutes 50-80% of the spontaneous forms.

- SECONDARY SPONTANEOUS PNEUMOTHORAX: lung collapse is always resulting from an "underlying lung disease. Symptoms are generally more pronounced than in the primary form and the severity of the clinical condition can be life-threatening (particularly if secondary spontaneous pneumothorax is not adequately treated).In most cases, secondary spontaneous pneumothorax affects people over the age of 40.

From the pathophysiological point of view, a "further classification of spontaneous pneumothorax can be made:

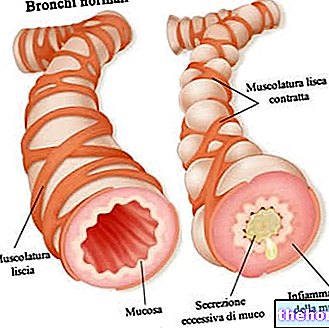

- Spontaneous open pneumothorax: the air enters and exits continuously from the pleural cavity, so the lung collapses completely, as it is subjected to the action of atmospheric pressure.

- Spontaneous closed pneumothorax: the lung is not completely collapsed, since the communication with the pleural cavity is closed, so there is no air leakage.

- Spontaneous valve pneumothorax (or tension pneumothorax): This is the most dangerous variant of pneumothorax. The air enters the pleural cavity during the inspiratory act, without going out during the exhalation: consequently, the intrapleural pressure increases exaggeratedly, to the point of literally crushing the lung. This clinical condition can jeopardize the patient's survival: pneumothorax hypertension can progress to induce restrictive ventilatory deficit and cardiovascular collapse.

Causes and risk factors

Spontaneous pneumothorax can result from a rupture of the pulmonary structures and visceral pleura: a similar condition favors the communication of the airways with the thoracic cavity, creating damage.

We have seen that only the secondary variant of spontaneous pneumothorax is related to lung diseases. The following are the morbid conditions most often observed in affected patients:

- AIDS

- lung abscess

- asthma

- COPD

- Cancer: primary lung cancer, carcinoid, mesothelioma, metastic sarcoma

- Chronic bronchitis associated with pulmonary fibro-emphysema

- thoracic endometriosis

- bullous emphysema (most cases)

- cystic fibrosis

- vascular infarction

- lung infections

- metastasis

- sarcoidosis

- Marfan syndrome (disease affecting connective tissue)

- ankylosing spondylitis

Although an apparently observable cause is not found in patients with primary spontaneous pneumothorax, it is assumed that the bubbles (accumulations of air developed inside the lung) and blebs (accumulations of air undermined between the lung and visceral pleura) can heavily affect the genesis of the disorder. It is estimated that videothoracicoscopy ascertains the presence of these bullous lesions in almost all patients with spontaneous pneumothorax.

Remarks:

The close correlation between the abrupt manifestation of spontaneous pneumothorax symptoms and the execution of an intense sporting practice is of great importance. In fact, it seems that pulmonary hyperventilation and muscular hyperactivity can be considered possible triggers. In this sense, the most popular sports weight lifting and diving are risky. However, it is conceivable that the appearance or persistence of a particularly angry cough can also cause the pneumothorax to burst.

Despite this, spontaneous pneumothorax appears suddenly in most patients, even at rest.

In-depth study: How can scuba diving affect the onset of pneumothorax?

During scuba diving, the air breathed through the self-contained breathing apparatus must have a pressure equal to that of the environment; the same air, however, increases in volume as the ambient pressure decreases, thus expanding in the ascent section. If the volume increase is excessive, it is conceivable the rupture of the pulmonary alveoli: in such situations, the passage of air inside the pleural cavity is favored, therefore the collapse of the lung (which results in pneumothorax).

Symptoms

Except for asymptomatic cases, the majority of patients affected by spontaneous pneumothorax complain of a peculiar "pleural" pain, limited to the hemithorax affected by the disease.

The clinical onset symptomatology depends on both the age of the patient and the extent of the pneumothorax. In affected children (spontaneous neonatal pneumothorax), for example, a flutter, a mediastinal vibration.

Many hospitalized patients report symptoms with expressions such as "violent." chest pain with dagger strike", often associated with more or less severe breathing difficulties. The dyspnea is clearly due to the collapse of the lung; young people seem to feel this disorder much more lightly than the elderly.

Furthermore, among the symptoms associated with spontaneous pneumothorax, agitation and the sensation of suffocation, reported by a good part of the patients, cannot be missing.

The patient with spontaneous pneumothorax appears in difficulty, often in an evident state of cyanosis. It is sometimes possible to detect tachycardia (> 135 bpm), jugular turgor due to involvement of the hollow veins and an increase in the size of the hemithorax affected by the disease.

Diagnosis

The chest X-ray detects the air accumulated inside the pleural cavity, the lowering of the diaphragm, the subcutaneous emphysema and the collapse of the lung towards the hilum.

The differential diagnosis must be made with:

- pleural effusion → the manifestation of symptoms usually occurs less abruptly than in spontaneous pneumothorax

- chest pain, pleurodynia (severe pain of the pleural nerves and intercostal muscles) and Bornholm disease (infection of the intercostal muscles, with possible involvement of the pleura) → characterized by an unpleasant and constant perception of breathlessness

- pulmonary embolism → among the symptoms we remember hemoptysis and rales at the level of the affected area

Therapy

In general, we speak of eclectic therapeutic conduct, in the sense that the therapy is heterogeneous and varied, because it is subordinated both to the triggering cause (when identifiable) and to the prediction of the spontaneous resorption of the lesion. When the damage is mild and affects a small portion of the lung, spontaneous healing is foreseeable: in such circumstances, absolute rest is recommended.

Several factors intervene in the choice of a therapy rather than another. It is necessary to take into consideration the severity of the symptoms, the age of the patient, the degree of respiratory distress and the underlying pathology (when detectable).

Even in the absence of symptoms (or in the case of mild distress respiratory) the newborn with spontaneous pneumothorax should be carefully monitored. Particular attention must be paid to monitoring heart and respiratory rate, arterial pressure and arterial oxygen saturation.

If necessary, oxygen can be administered for a few hours in order to reduce the pneumothorax and speed up healing.

For the adult man and for the young man suffering from spontaneous pneumothorax, the therapy of choice is the pleural drainage by gravity or suction, very useful both for the removal of intrapleural air and to prevent any further accumulation.

Medical statistics show that chest drainage to treat the first episode of spontaneous pneumothorax has a very high success rate, estimated at around 90%. However, in case of relapses, this value drops to 52% (for the first relapse) and to 15% for the second.

In the event of recurrent relapses or failure to respond to pleural drainage, a surgical treatment is conceivable. Pelurodesis (favors the adhesion of the lung to the chest wall) or pleurectomy (partial surgical excision of the parietal pleura) are the surgical treatments of choice for the treatment of pneumothorax.

In some particular conditions, surgery is recommended already at the first episode of spontaneous pneumothorax. In such situations, surgery is the therapy of choice in case of:

- haemopneumothorax (accumulation of air and blood in the pleural cavity)

- bilateral pneumothorax

- regressed history of contralateral pneumothorax

- hypertensive pneumothorax

In conclusion, it is necessary to seek medical assistance even in the case of suspected beginning of pulmonary collapse: in cases of extreme severity, in fact, an inadequately treated pneumothorax can degenerate up to the induction of cardiac arrest, shock, hypoxemia, respiratory failure and death.

.jpg)