Generality

Helicobacter pylori is the name of a GRAM-negative bacterium, 2.5-5 μm long, capable of colonizing the mucous membrane of the stomach; the consequent infection establishes a local inflammatory picture, which can progress towards important pathologies such as chronic gastritis, non-ulcer dyspepsia, peptic ulcer and stomach cancer.

Although the intraluminal environment of the stomach is such as to prevent the growth of the vast majority of microbial forms, Helicobacter pylori has developed various survival strategies, to the point of being able to infect more than 50% of the world population.

Fortunately, in most cases (about 80-85%) the infection manifests itself in asymptomatic or modest forms.

In-depth articles

The bacterium Epidemiology Pathogenicity Contagion and prevention Symptoms Diagnosis Treatment Natural remediesThe bacterium

The story of Helicobacter pylori begins in 1983 thanks to Robin Warren and Barry Marshall, the two Australian doctors who first succeeded in demonstrating the presence of a spiral-shaped microorganism in gastric mucosal biopsy samples. Until then, the medical community was absolutely convinced that it was not possible for bacteria to take root and develop in the stomach, considering the highly acidic pH and the marked digestive enzymatic activities that characterize it.

Thanks to numerous studies on Helicobacter pylori, various mechanisms have been identified by which this germ manages to survive in such a hostile environment:

- Helicobacter pylori is a microaerophilic bacterium: as such it is able to grow without problems even in a poorly oxygenated atmosphere;

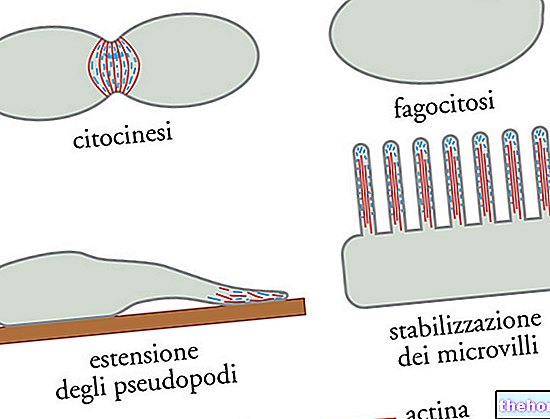

- The helicobacter pylori has a spiral shape and is equipped with flagella at the polar end: thanks to these characteristics it is able to produce a "corkscrew" movement which, together with the production of mucinase, allows it to penetrate the mucus barrier that protects the gastric mucosa;

- Helicobacter pylori is equipped with adhesins and glycocalyx, which, if necessary, allow it to adhere to the gastric epithelium while remaining immune to peristaltic movements and to the continuous replacement of the mucous layer that protects the gastric walls;

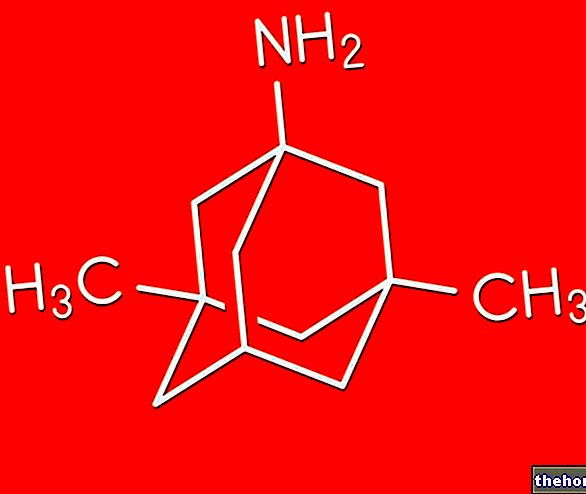

- Helicobacter pylori shows a marked urease activity: once the bacterium has penetrated the mucous layer, it finds an ideal habitat, capable of repairing it both from the action of the acid present in the stomach and from that of antibodies. The chances of survival of the bacterium they are further enhanced by its ability to produce urease, an enzyme that breaks down urea into carbon dioxide and ammonia. Due to its basicity, this substance neutralizes the acid produced in the stomach, ensuring an ecological niche with a pH suitable for the growth of helicobacter pylori. Ammonia (NH3) has in fact the ability to capture the H + protons supplied by water (H + + OH-), with the formation of ammonium ions on one side (NH4 +) and bicarbonate on the other (HCO3- thanks to the combination of "hydroxyl OH- of" water with carbon dioxide CO2).

- Enzymes such as catalase and superoxide dismutase, which protect bacteria from the bactericidal effect of immune cells, also contribute to the survival of infecting colonies. Furthermore, in hostile conditions, Helicobacter pylori takes on coccoid form, which gives it resistance properties both in stomach than in the environment.

Epidemiology

Given its great nesting and survival capacity in the gastric environment, Helicobacter pylori is responsible for a particularly widespread infection, so much so that it affects about half of the world population. As regards the industrialized countries, it is estimated that the incidence coincides approximately with the decade of age they belong to. Thus, for example, in the age group between 40 and 50 years, the incidence is estimated at around 40 -50% of the population. This trend proportional to age is however lost after 60-65 years, probably due to the greater diffusion of atrophic gastritis, which in the affected subjects generates an unfavorable environment for the microorganism.

The progressively increasing trend of the incidence up to the age of 60 can be explained by considering that older individuals are more likely to have lived in more unfavorable sanitary conditions than subsequent generations ("cohort effect"). Not surprisingly, the prevalence is higher in developing countries and it is no coincidence that Helicobacter pylori infection is contracted almost exclusively in childhood, especially under the age of ten; for this reason, thanks to improved hygienic and socio-economic conditions, today's children have a much lower probability of being infected than a few decades ago.

As we will see in the following paragraphs, despite the prevalence of infection being on average around 30-65% of adults and 5-15% of children, in the vast majority of cases it remains completely asymptomatic. In the absence of effective antimicrobial therapy However, after being contracted, Helicobacter pylori infection can persist for a lifetime.

Other articles on "Helicobacter pylori"

- Helicobacter pylori: Pathogenicity

- Helicobacter pylori: Contagion and Symptoms

- Helicobacter pylori: Diagnosis and Treatment