Generality

Neutropenia is a reduction in the number of neutrophilic granulocytes circulating in the blood. If severe, this condition increases susceptibility to infection.

There are also familial (associated with genetic alterations) and idiopathic forms of neutropenia (the cause of which is unknown).

Usually, neutropenia remains asymptomatic until an infectious state develops. The resulting manifestations can be variable, but fever is always present during the most serious infections.

The diagnosis is made through the evaluation of the blood count with a leukocyte formula; however, it is also important to identify the triggering cause, in order to correct, where possible, the situation and establish the most appropriate treatment.

In the presence of marked neutropenia, a broad spectrum empirical antibiotic therapy should be started immediately.

Treatment may also include the administration of granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) and the adoption of supportive measures.

What are neutrophils?

Neutrophils make up 50-80% of the leukocyte population (set of white blood cells present in the blood).

Under physiological conditions, these immune cells play a crucial role in the body's defense mechanisms against foreign agents, especially infectious ones.

Neutrophils are capable of operating phagocytosis, that is, they incorporate and digest microorganisms and abnormal particles present in the blood and tissues. Their functions are perfectly linked and integrated with those of the monocyte-macrophage system and lymphocytes.

Adult blood normally contains 3,000 to 7,000 neutrophils per microliter. The organ that produces these cells is the bone marrow, where stem cells proliferate and differentiate to morphologically recognizable elements as myeloblasts. Through a series of maturative processes, these become granulocytes (so defined by the presence in their cytoplasm of vesicles containing enzymatic complexes organized in clearly visible granules).

The newly formed neutrophils circulate in the blood for 7-10 hours, to migrate into the tissues, where they live only for a few days.

Risk of infections

The minimum value of neutrophil granulocytes considered normal is 1,500 per microliter of blood (1.5 x 109 / l).

The severity of neutropenia is directly related to the relative risk of infections, which is greater the closer the number of neutrophils per microliter approaches zero.

In any case, neutropenia depends on the absolute neutrophil count, defined by multiplying the number of total white blood cells by the percentage of neutrophils and their precursors.

On the basis of the value thus calculated, it is possible to divide the neutropenias into:

- Mild (neutrophils = 1,000 to 1,500 / microliter of blood);

- Moderate (neutrophils = 500 to 1,000 / microliter);

- Severe (neutrophils

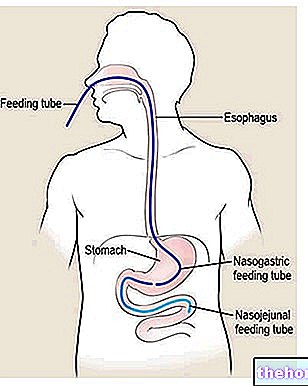

When the count falls to less than 500 / microliter, the endogenous microbial flora (such as that present in the oral cavity or in the intestine) can establish infections.

If the neutrophil value decreases beyond 200 / microliter, the inflammatory response may be inefficient or absent.

The most extreme form of neutropenia is called agranulocytosis.

Causes

Neutropenia can depend on the following pathophysiological mechanisms:

- Defect in the production of neutrophil granulocytes: it can be the expression of a nutritional deficiency (eg vitamin B12) or of a neoplastic orientation of the hematopoietic stem cell (eg myelodysplasias and acute leukemias).

Furthermore, the lack of or reduced production of neutrophils can be the effect of genetic alterations (as occurs in the context of different congenital syndromes), damage to the stem cell (medullary aplasia) or replacement of hematopoietic tissue by neoplastic cells ( e.g. lymphoproliferative diseases or solid tumors). - Abnormal distribution: it can occur due to an excessive sequestration of circulating neutrophils in the spleen; a typical example is the hypersplenism characteristic of chronic liver diseases.

- Reduced survival due to increased destruction or greater utilization: the margination in the tissues and the sequestration of neutrophils recognizes a genesis of various kinds (eg drugs, viral infections, idiopathic, autoimmune diseases, etc.).

Acute and chronic neutropenia

Neutropenia can be short or long lasting.

- Acute neutropenia occurs within a period of a few hours to a few days; this form mainly develops when the use of neutrophils is rapid and their production is lacking.

- Chronic neutropenia lasts for months or years and generally results from reduced production or excessive splenic sequestration of neutrophils.

Classification

Neutropenias can be divided into:

- Neutropenies due to intrinsic defects of myeloid cells or their precursors;

- Acquired cause neutropenia (i.e. due to extrinsic factors to myeloid progenitors).

Classification of neutropenia

Intrinsic defect neutropenia

- Severe congenital neutropenia (or Kostmann syndrome)

- Benign familial neutropenia of Gänsslen

- Severe familial Hitzig neutropenia

- Reticular dysgenesis (alymphocytic neutropenia)

- Shwachman-Diamond-Oski syndrome

- Familial cyclic neutropenia

- Congenital dyskeratosis

- Neutropenia associated with dysgammaglobulinemia

- Myelodysplasia

Acquired neutropenia

- Post-infection

- From drugs

- Alcoholism

- Hypersplenism

- Autoimmune (including secondary chronic neutropenia in AIDS)

- Associated with folate or vitamin B12 deficiency

- Neutropenia secondary to radiation, cytotoxic chemotherapy and immunosuppression

- Bone marrow replacement from malignant tumors or myelofibrosis

- T-γ-cell lymphoproliferative disease

.jpg)