See also: colon

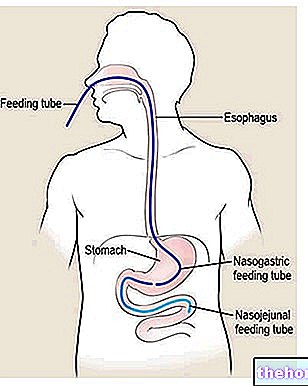

The large intestine represents the terminal part of the digestive tract. About two meters long, it extends from the ileocecal valve to the anus. Anatomically it is divided into six sections which, in the aboral direction, are respectively called: cecum, ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, sigma and rectum.

Although its length is about four times shorter than that of the "small intestine, the large intestine has a" similar capacity, thanks to a much greater diameter.

At the level of the small intestine, food digestion is completed and a large part of the nutritional principles obtained (about 90%) is absorbed. The primary function of the large intestine is therefore to accumulate the residues of the digestive process and favor their expulsion.

The absorbent capacity of the large intestine is however important since, especially in the colon, there is a considerable absorption of water and electrolytes. The longer the digestive products remain in the large intestine, the greater will be the reabsorption of water and salts. This phenomenon becomes evident in case of diarrhea (loss of salts and water) or constipation (particularly hard, compact and dehydrated stools).

Vitamins are also absorbed in the large intestine, not so much those introduced with food (already absorbed in the small intestine), but above all those produced by the billions of symbiotic bacteria that populate the colon. These microorganisms synthesize in particular vitamin K and some vitamins of group B.

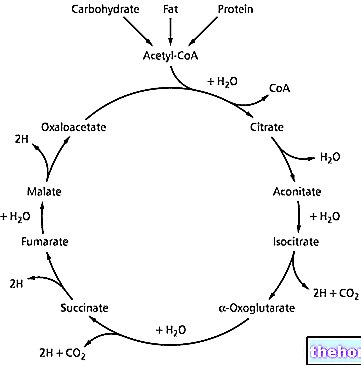

To live, the intestinal bacterial flora derives the energy necessary for its sustenance from the digestion of dietary fiber and other products (especially sugars) which are indigestible for man. From the bacterial degradation of the fiber, short-chain fatty acids are formed, in particular butyric acid and propionic acid, which are also absorbed in the large intestine. Our body is able to use these fatty acids to obtain energy. For this reason it is not correct to say that fiber is calorie-free, without specifying that its modest caloric intake is compensated by the loss of nutrients linked to its chelating and laxative properties.

Butyric acid produced by the bacterial flora that populate the large intestine appears to have a protective effect against colon cancer. Hence the healthy recommendation to enrich one's diet with a "wide variety of fresh vegetables and whole foods, often excluded from the dietary habits of Westerners.

The large intestine also acts as a "deposit" for faeces, thanks to a much larger diameter than that of the small intestine. As mentioned previously, the colon also has the property of concentrating digestion residues and, ultimately, of promoting their expulsion. By absorbing water and increasing fecal mass, dietary fiber and supplements that contain it stimulate intestinal motility. , facilitating evacuation. When they are not supported by an "abundant supply of liquids, the laxative effects of the fiber are modest.

The duration of digestion is related to the quantity and quality of the food ingested. An average meal remains in the stomach for about 2-3 hours, remains in the small intestine for another 5-6 hours and, once it reaches the large intestine, stays there for about 48-72 hours.

The faeces, excreted outside through the anus, are mainly made up of water (75%), bacteria, fats (since their digestion is more complicated than that of other nutrients), inorganic substances (minerals and in particular calcium, iron , zinc), proteins, undigested material (especially fiber) and desquamated enterocytes.