Introduction

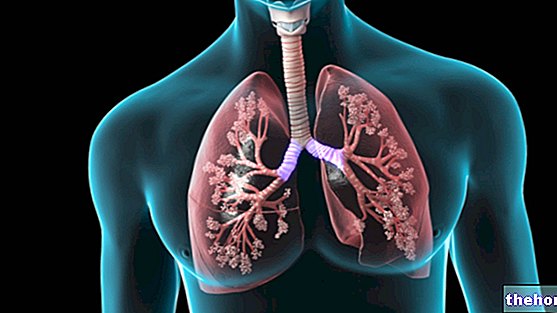

Although they usually populate the respiratory mucous membranes without causing damage, pneumococci, finding the optimal conditions for them, can replicate themselves immeasurably by transforming themselves from commensal microorganisms to terrible opportunistic pathogens, capable of triggering diseases of varying extent.

In the previous discussion we described the pneumococcus from a microbiological point of view, also focusing on the epidemiological aspects; in the following discussion, the topic will be deepened from the point of view of diseases, thus examining the pathogenesis, the symptomatological picture and the treatments available.

- Pneumococcal infections: pathogenesis

- Pneumococcus pneumoniae And Haemophilus influenzae

- Pneumococcal Infections: Symptoms

- Symptoms INVASIVE pneumococcal infection

- Symptoms of pneumococcal pneumonia

- Symptoms NON-invasive pneumococcal infection

- Pneumococcal infections: diagnosis

- Pneumococcus: therapies

Causes

The cells of the pneumococcus reach the alveolar level by inhalation of infected micro-droplets of saliva; only minimally can the bacilli spread by hematogenous route.

TO DEVELOP THE DISEASE, THE PNEUMOCOCCUS MUST PASS THROUGH THE MUCOUS BARRIERS OF THE HOST; it should also be remembered that only pneumococci equipped with a capsule they are virulent.

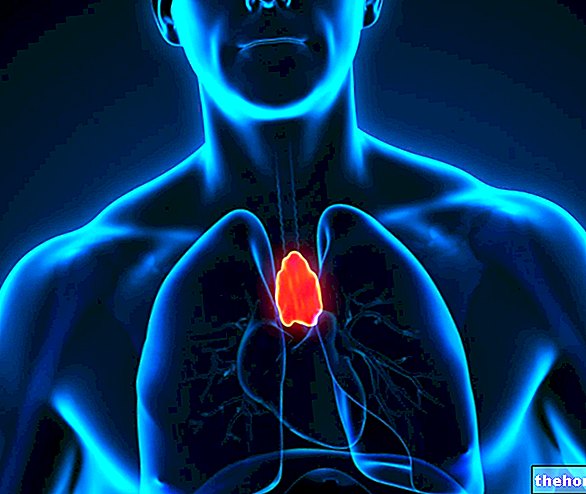

After passing the mucous membrane of the respiratory tract, the pneumococcus can reach the nasal sinuses and the middle ear; if the bacterium manages to overcome the body's defenses, thus escaping the action of the immune system, it can spread to the point of creating pneumonia, meningitis and mastoiditis (inflammation of the mastoid cells following infection in the middle ear). Later, from lung lesions the pneumococcus can infect the mediastinal lymph nodes, pass into the thoracic duct and, ultimately, into the bloodstream (bacteremia). If the infection proceeds, vital organs, such as the heart, can also be affected: here, pneumococcus can cause endocarditis and pericarditis. In some patients, infection occurs in the joint cavities.

The inhalation of infected secretions is slowed down by the normal closure of the epiglottis during swallowing; the movements of the cilia along the airways can also defend the body from pneumococcal attacks, since they can carry infected mucous secretions from the lower respiratory tract to the pharynx and middle ear.

A healthy subject is normally able to block the infection in the bud; moreover, it has been observed that the co-presence of other bacilli on the respiratory mucosa, such as Haemophilus influenzae, severely limits (or even blocks) pneumococcal replication.

Deepening: Pneumococcus pneumoniae And Haemophilus influenzae

Also Haemophilus influenzae it is involved in infectious diseases affecting the respiratory tract and, similarly to pneumococcus (and meningococcus), can also cause damage to the meninges. It is not uncommon for the two pathogens to be found simultaneously in the same site; in such circumstances, however, only one bacterium survives: between the two, the pneumococcus is destined to succumb. If the two microorganisms (H. influenzae and pneumococcus) were SEPARATELY located in the nasal cavities, a similar situation would not occur, and both would be able to cause damage.

How to explain this phenomenon?

In the laboratory, some experiments on animal guinea pigs have led to surprising results: analyzing the respiratory tissue of a mouse exposed to both bacteria, an exaggerated number of neutrophils was observed, expression of the mobilization of cells of the immune system. However, when the respiratory tissue of the mouse was exposed to only one of the two bacteria it triggered a much lower immune response.

- From the laboratory results, it appeared that neutrophils previously exposed to Haemophilus influenzae exert greater aggression towards pneumococci than neutrophils NOT exposed to H. influenzae.

What conclusions can be drawn?

The mechanism governing this particular competition is not yet clear with certainty; however, two hypotheses have been formulated:

- The co-presence of Haemophilus influenzae and Pneumococcus pneumoniae triggers a particular and typical immune response; in the event of an attack by a single pathogen, the defense system does NOT mobilize in this way

- When Pneumococcus pneumoniae attacks Haemophilus influenzae, the immune system is stimulated to attack the pneumococcus

The antigens of the polysaccharide capsule are essential elements to ensure virulence to the pneumococcus; moreover, the antigens guarantee the microorganism a certain protection from macrophages and polynuclear cells, which could engulf - therefore inactivate - the pathogen.

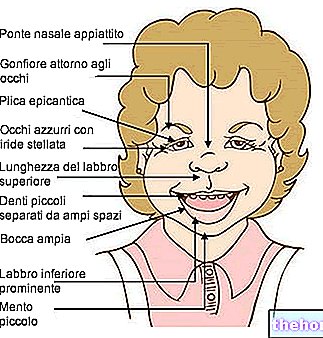

Young children under the age of two are particularly sensitive to pneumococcal infections, since the organism is not yet able to produce antibodies to polysaccharide antigens.

General symptoms

Pneumococcal infections are classified into two categories: invasive and non-invasive. In the first category, pneumococcal infection is completed within a vital organ or in the blood, and the damage is extremely severe; the non-invasive forms occur outside the sites just described, and generally create limited and easily resolved damage.

The table summarizes the symptoms that distinguish the various invasive infections mediated by pneumococcus.

Symptoms table

INVASIVE pneumococcal infection

Symptoms

Septic arthritis (infection in one "joint)

Fever, severe pain, inability / inability to control the joint involved in the infection

Bacteremia (spread of bacteria in the blood)

Presence of bacteria (pneumococcus, in this case) in the blood, with fever and other non-specific symptoms

Meningitis (inflammation of the meninges)

Anorexia, menstrual changes, widespread chills, convulsions, joint and muscle pain, migraine, high fever, photophobia, irritability, nausea, cough and vomiting

Osteomyelitis (bone and bone marrow infection)

Redness and swelling of the affected area, difficulty moving the injured area, acute pain, fever and potential swelling. Possible formation of skin fistulas with emission of pus

Pneumonia (infection of the lungs)

Omnipresent symptoms: chills, severe chest pains and cough. Pneumonia is also characterized by: bad breath, weakness, dyspnoea, muscle aches, headache, sweating, rapid breathing

Septicemia (alarming and exaggerated Systemic Inflammatory Response following a pneumococcal bacterial insult - in this case)

Hypothermia / high fever, increased respiratory rate, tachycardia + cardiac dysfunction, gangrene, hypotension, leukopenia, patches on the skin, loss of organ function, thrombocytopenia, diffuse thrombus, death.

Pneumococcal pneumonia

The most common disease triggered by pneumococcus is PNEUMONITIS, often preceded by purely flu-like symptoms. The intensity of the symptoms depends on the general health of the patient and the pneumococcal serotype involved in the infection. Even the onset of symptoms is not always constant and some patients first develop very mild symptoms, an element that complicates the diagnosis, making the pathology even more dangerous and subtle.

Severe pneumonia usually begins with a very high fever, which can reach 40-41 ° C in a few hours; clearly, the exaggerated thermal increase also involves the development of widespread chills (the so-called shaking thrill). Some patients with pneumococcal pneumonia also complain of chest pain, dyspnoea, cyanosis, polypnea, and tachycardia. The cough, omnipresent, is initially dry and irritating, and then turns into a fat cough, with the production of a sputum streaked with blood, with a yellow-greenish hue. Secondary symptoms are also possible, such as asthenia, arthomyalgia, diarrhea, abdominal distension, nausea and vomiting.

It is not uncommon for the patient to contract Herpes labialis in association with pneumonia.

The table shows the characteristic symptoms of NON-invasive pneumococcal infections.

NON-invasive pneumococcal infection

Symptoms

BRONCHITIS (bronchial infection)

Difficulty swallowing, dyspnoea, joint pain, greenish-white sputum emission, pharyngitis, fever, flu, cold, hoarseness.

Conjunctivitis (infection of the conjunctiva)

Redness and swelling of the conjunctiva, lacrimation, ocular itching, conjunctival hyperaemia, lymphadenopathy

OTITIS MEDIA (middle ear infection, typical of children under the age of 10)

Ear pain to touch (otitis externa), discharge of purulent material from the ear canal associated with pain (otitis media), sore throat, fever, low-grade fever, stuffy nose, cough

SINUSITIS (sinus infection, small air-filled cavities, located behind the cheekbones and forehead)

Nasal obstruction with release of yellowish or greenish mucus + altered perception of food taste, bad breath, nasal congestion, weakness, dyspnoea, facial and tooth pain, fever, swollen eyes, closed ears, runny nose and cough

Diagnosis of infections

Before embarking on a therapeutic strategy for the treatment of the infection, it is necessary to ascertain the pathogen involved in the disease: the samples on which it is possible to isolate the bacterium are blood (for blood culture) and sputum (for culture analysis and microscopic). Many streptococci are morphologically similar, so it is easy to confuse one strain with another; for this reason, the culture of the bacterium is always indispensable. However, microscopic analysis of a sample of purulent material, CSF or sputum is useful to suspect pneumococcal infection and possibly initiate targeted therapy while awaiting the results of the culture analysis.

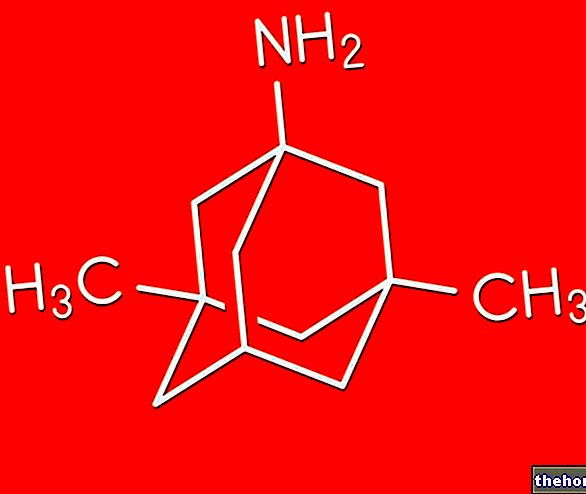

The optokine test (a-ethylhydrocuprein) identifies and distinguishes the pneumococcal colonies from any other viridating streptococci, very similar from the morphological point of view: unlike the other streptococci, the pneumococcus appears to be sensitive to the optokine.

Furthermore, the bile salt sensitivity test is used for diagnostic purposes to highlight pneumococci: in the presence of bile salts (sodium deoxycholate 0.05%), the pathogens belonging to this category undergo lysis in a very short time.

The Omniserum agglutination test (a particular capsular swelling reaction), is used instead to agglutinate all types of pneumococcus.

For an even more in-depth diagnostic investigation, it is necessary to make use of the so-called TYPING, therefore the exact identification of the type of pneumococcus involved in the infection: for this investigation, it is possible to use the Neufeld reaction (or capsular swelling) or the " slide agglutination.

Contrary to what one might think, the search for antibodies against antigens is not used among the diagnostic techniques, since the types of antigens that can be involved in pneumococcal infection are very numerous.

However, it seems that the best diagnostic investigation for an invasive pneumococcal infection is the polymerase chain reaction (or more simply PCR), although this technique is not very widespread.

The search for pneumococcal polysaccharide in a urine sample is not recommended: in fact, this diagnostic investigation has proved not very specific for pneumococcal infections.

Care

Pneumococcus shows a moderate sensitivity to some antibiotics, in particular to penicillins, erythromycin and tetracyclines. Despite what has been said, there are reports of drug resistance, especially penicillins: in the USA, it is estimated that 5-10% of pneumococci responsible for infection are completely resistant to these drugs, while 20% are considered moderately resistant.

Resistance to penicillin is a consequence of the alteration of the proteins that bind the drug, not so much of the synthesis of beta lactamase.

In general, pneumococcal infections should be treated with the combination amoxicillin + clavulanic acid; cephalosporins are also drugs indicated for eradicating pneumococcal infections.

More articles on "Pneumococcus - Infection, Symptoms, Diagnosis, Therapy"

- Pneumococcus

- Pneumococcal Vaccination - Anti-Pneumococcal Vaccine