After having talked about "osteoarthritis in general and having deepened that of the knee and cervical tract, today it is the turn of hip osteoarthritis, also called coxoarthritis.

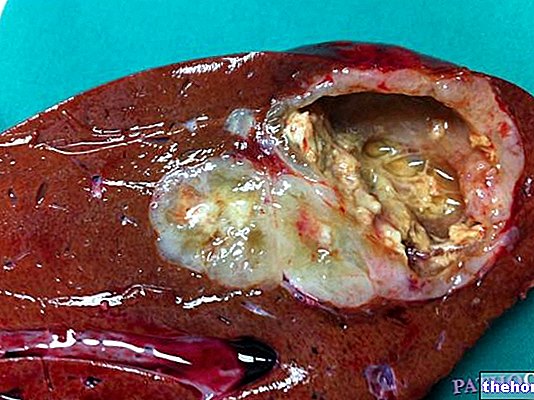

Coxarthrosis is a degenerative process that affects the hip joint. It is undoubtedly one of the most important forms of osteoarthritis, both for the frequency with which it occurs in the population, and for the serious disability that can ensue. Like all forms of osteoarthritis, even that of the hip is a chronic disease that gradually consumes the articular cartilages. In particular, in coxoarthrosis the layer of cartilage that covers the head of the femur and the cavity of the "hip in which it articulates; this circular bone cavity is called the acetabulum of the hip, while the head of the femur corresponds to the distal epiphysis of the bone. , minimizing the friction during the movements. Consequently, the wear of the cartilage first determines a chronic pain in the hip, reducing the fluidity of the movements; subsequently, the damage to the cartilage also extends to nearby tissues that participate in joint movement, so the symptoms of osteoarthritis worsen as a result. In fact, when the cartilage lining thins to the point of exposing the underlying bone, the latter reacts. thickening and producing bone spurs, called osteophytes, at the ends of the joint surface. In the more advanced stages of osteoarthritis, the joint capsule thickens and the muscles retract to cause severe deformity; the hips are thus locked in semi-flexion, rigid and rotated outwards. At the same time, the pain increases and with it the limitation. movement is therefore increasingly compromised and the degree of disability increases over the years, making it difficult even to simply walk. In such severe circumstances, only surgery with the implantation of an artificial prosthesis can solve the problem.

The causes of coxarthrosis are many. First of all, it may be useful to distinguish the various forms of osteoarthritis into primary and secondary. In the primary forms, it is not possible to identify a precise cause of origin, while the secondary forms of osteoarthritis are consequent, indeed secondary, to other pathologies, disorders or traumas, for example to congenital diseases of the hip, fractures, joint infections or other pathologies. Primary coxarthrosis is a typical disease of advanced age. Aging plays, in fact, a predominant role in the wear of the articular cartilage. It is therefore no coincidence that hip arthrosis typically arises after the age of 60. age. To determine its onset are general factors, since the causes of a pathological type are the prerogative of secondary forms. Just to give a few examples, if a patient weighs too much or carries out a work or sporting activity that places heavy stress on the joint, they will be more likely to have hip arthrosis. Secondary forms of arthrosis can affect younger patients. , even of 30-40 years. As we have mentioned several times, in secondary coxarthrosis, unlike the primary form, a known cause is recognized. Almost always it is trauma or local damage that irreversibly damages the joint, for example fractures, dislocations or inflammatory processes.In other cases, coxarthrosis may be the consequence of congenital malformations of the joint itself, therefore present from birth as in the case of congenital hip dysplasia. On the other hand, cases of secondary coxarthrosis linked to systemic disorders, such as the presence of dysmetabolic or endocrine diseases, such as diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis or gout, are rarer.

As with all other forms of osteoarthritis, the typical symptoms of coxarthrosis are pain and limitation of movement. Both tend to get worse over time. The pain is felt in the groin or in the front of the thigh, while the location in the buttock is rarer. In other cases, pain can be felt in the outer thigh region and can go down to the knee. An important feature of pain is its progressive evolution; if initially it is accused while walking or after prolonged efforts, and then lessens with rest, in the more advanced stages the pain tends to persist over time. Clearly, pain goes hand in hand with restriction of movement. When osteoarthritis affects the hip joint, it can be difficult to get out of the bath, get on a bicycle, or squat down to put on a shoe.

The symptoms we have just seen are typical of hip osteoarthritis and can guide the doctor towards a correct diagnosis. During an orthopedic evaluation, in addition to investigating the nature of these symptoms, their trend over time and the correlation with any risk factors, the doctor will also personally appreciate the degree of movement limitation. To confirm the diagnostic suspicion, and to obtain an accurate picture of the joint damage, radiological examinations are necessary. In advanced stages, a simple X-ray clearly shows the typical signs of osteoarthritis even to an inexperienced eye.

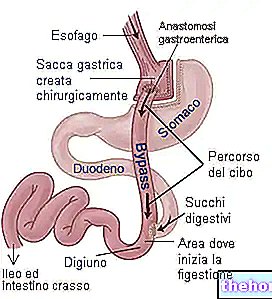

For example, as shown in the figure, you can see the reduction of joint spaces and bone thickening below the worn cartilage. Furthermore, the presence of osteophytes is evident, which we have seen to be small bone spurs, while in some cases geodes are also appreciated, which are limited areas of bone resorption.

As for the options for cure and treatment, pain relievers or anti-inflammatories can certainly provide pain relief in the early stages of the disease. It is, however, a simple palliative; as with other forms of arthrosis, in fact, these drugs are not able to limit or even reverse joint damage, which will therefore continue to worsen inexorably little by little. Furthermore, it is necessary to be careful not to abuse these drugs, such as ibuprofen or naproxen, because they are not entirely without side effects. Always in the initial stages, when the cartilage degeneration is still partial, infiltrations can be useful. In practice, the doctor performs intra-articular injections of chondroprotective agents, such as hyaluronic acid, which slow down the destruction of cartilage and the progression of the disease. In the face of advanced stage hip arthrosis, the most effective treatment is surgical and involves the implantation of a prosthesis; in other words, an artificial joint is inserted that copies and replaces the natural diseased joint. In practice, however, the situation is not so simple, since there are complete and partial prostheses, made of different materials and which require different surgical procedures; the choice, as always, must be made on the basis of the characteristics of the individual patient. In general, however, the intervention immediately eliminates arthritic pain and considerably improves the patient's quality of life, restoring at least part of the lost movement.

Weight loss, i.e. the reduction of body weight, is certainly a priority in overweight or obese patients. In fact, this allows to reduce the overload that weighs on the joint, preventing cartilage damage or in any case reducing its progression. Furthermore, in anticipation of surgery, the reduction of body weight allows to reduce possible complications and accelerate post-operative physiotherapy. The same benefits of weight loss are to be attributed to the start of a specific physical exercise program, to strengthen the muscles, maintain hip mobility, slow down the arthritic process and promote faster recovery from surgery. Activities are recommended. physical without load, such as swimming or cycling, while jogging and all contact sports should be avoided, as they could accelerate the degeneration of joint tissues.