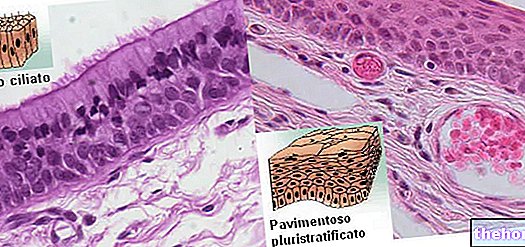

INTRODUCTION: Articular cartilage is a highly specialized connective tissue made up of cells called chondrocytes and the surrounding supporting tissue, the matrix. It has a pearly white color and covers the ends of the joint bones, protecting them from friction. Its function is similar to that of a shock absorber, capable of safeguarding normal joint relationships and allowing movement.

Due to the complete absence of vascularization and innervation, the cartilage shows poor regenerative capacity in case of injury, especially if it is severe. Even when this regenerates, it still gives rise to a fibrocartilage type tissue, less resistant and elastic than the original; it can therefore compromise the functionality of the joint and favor the onset of degenerative phenomena over time (arthrosis or osteoarthritis).

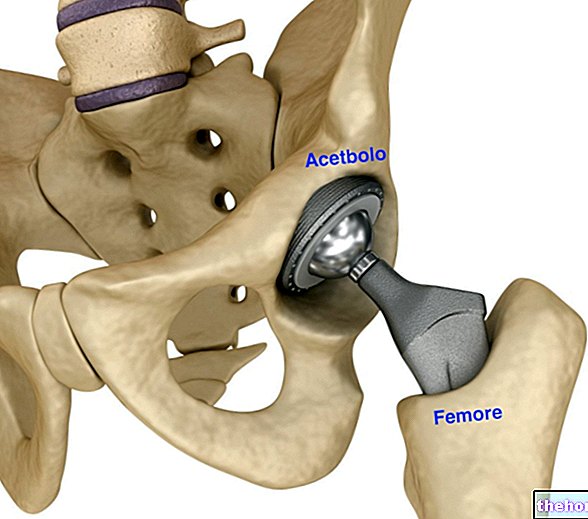

Cartilage lesions are a very common problem, easily found in the elderly (degenerative osteoarthritis), but sometimes also in the young, where damage of traumatic origin occurs more frequently with a high risk of evolution into arthritic forms. Until a few years ago, the possibilities treatments were limited and the patient was condemned to disability or, where possible, to replace the joint with a joint prosthesis. Today, modern surgical techniques associated with tissue engineering offer some more hope.

It is possible to stimulate the bone marrow to form reparative fibrocartilage tissue, making multiple small holes (perforation), causing microfractures or filing the surface of the subchondral bone (bony portion under the cartilage); as mentioned a few lines ago, the repair tissue that is formed is of the fibrocartilaginous type (of series B) and as such has a much lower functionality than the cartilage provided by mother nature. For this reason, these techniques are currently indicated in the treatment of shallow and modest chondral lesions.

In case of more extensive lesions it is possible to opt for a cartilage transplant.

Cartilage transplant

It is good to clarify, first of all, that this term refers not to one, but to three different surgical techniques.

→ Perichondrium or periosteum implants (thin membranes that cover, respectively, the cartilage, except the joint portions, and the bones, except the articular surfaces and the insertion points of the tendons). The surgeon takes flaps of these tissues and inserts them into the injured area, where they induce the growth of a tissue similar to cartilage or fibrocartilage.

INDICATIONS: The long-term results are contradictory; for this reason it is not a widespread technique.

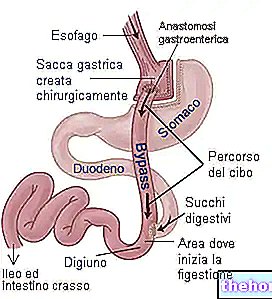

→ Mosaicoplasty or osteochondral graft: involves the use of cylinders of osteochondral tissue (ie bone portions with the overlying cartilage) taken from the injured joint of the same patient and pressure grafted into the cartilage defect.

INDICATIONS: this cartilage transplant can be performed arthroscopically, therefore it is minimally invasive and does not cause rejection and infection problems. It is performed at the same surgical time and is indicated only for small lesions, while the depth is not a limiting factor; for obvious reasons the osteochondral material necessary for the graft is in fact limited and higher samples would cause significant damage at the donor site. The cartilage transplant is therefore the result of a compromise: a "critical area for the functionality of the joint" is "repaired" taking the cartilage from a less important area, but not for this useless or superfluous.

Cartilage transplantation cannot be performed for inoperable joints, such as those in the fingers, foot or spine; it is instead indicated for the knee, ankle, shoulder and hip.

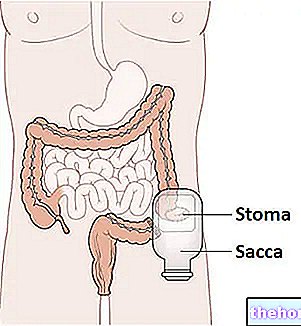

→ Autologous chondrocyte transplantation: cartilage cells are harvested from the patient by removing a small slice of cartilage in a non-loaded area. Using biotechnological techniques, the chondrocytes taken are isolated and cultured in the laboratory for 2-4 weeks, during which they differentiate by multiplying their number. At this point the patient undergoes a new operation, during which the lesion is cleaned and covered with the periosteum, leaving a small hole through which the cultured cells will then be injected. The periosteal flap, taken from the antero-medial surface of the ipsilateral tibia, is responsible for any complications that may arise within a short time; moreover, it requires a rather complex surgical technique, which cannot be performed arthroscopically. To overcome these problems, autologous chondrocyte implants can be used on hyaluronic acid support of biotechnological origin, which also have the advantage of requiring a less invasive surgical technique. The research is currently aimed at the identification of new biotechnological supports, able to favor the engraftment and proliferation of transplanted chondrocyte cultures, according to the characteristics of the "natural" articular cartilage.

Also in this case, since the patient is a donor and a recipient at the same time, there are no problems with rejection or infection. Contrary to the previous technique, the limiting factor is not so much the extension of the lesion, but its depth: if the damage is extended to the underlying bone (severe injuries, osteochondritis, advanced arthrosis) the implant takes root with difficulty, since it lacks of the bone support described in the previous case. Biotechnological materials are therefore being sought that act as a suitable support, in order to avoid the dispersion of the chondrocytes in the surrounding environment and favor their growth even in the presence of currently untreatable pathologies.

NOTES: both treatments based on perforations, abrasions and microfractures, and those involving cartilage transplantation are indicated for patients under the age of 40-50, since aging decreases the proliferative capacity of the cartilage, up to zero. None. of the techniques reported in this article is valid for advanced osteoarthritis.

.jpg)