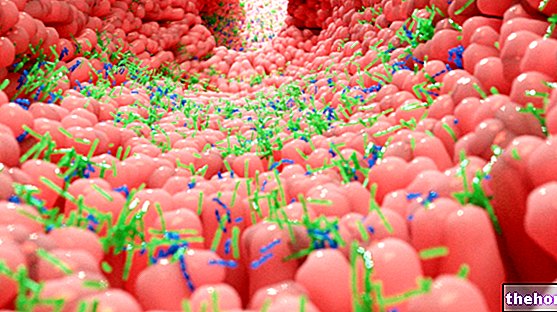

Small intestine bacterial contamination syndrome - also known as small intestine bacterial overgrowth syndrome (Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth - SIBO) - is characterized by the excessive proliferation of bacteria, especially anaerobic, in the lumen of the small intestine (or small intestine).

The overgrowth of bacteria in the small intestine compromises the ability to digest and absorb nutrients, especially lipids, triggering the classic symptoms of malabsorption syndromes: flatulence, bloating and bloating, steatorrhea, diarrhea and intestinal disorders in general.

Bacterial contamination of the small intestine: causes and risk factors

It is believed that the bacterial flora housed in the upper tracts of the digestive system and the small intestine is mostly represented by contaminants ingested in transit to the colon. There are numerous mechanisms that prevent the overgrowth of bacterial populations in these tracts: acidity gastric, the antibacterial power of biliary and pancreatic secretions, the intense peristaltic activity of the small intestine, the tightness of the ileocecal valve, the mucus and IgA immunoglobulins secreted by the intestinal mucosa and its rapid turnover.

From what has been said, it is clear how the various anatomical and / or functional conditions that compromise these defensive mechanisms can favor the onset of the bacterial contamination syndrome of the small intestine:

- risk factors such as malnutrition, immunological deficits, aging, hypochlorhydria (gastric atrophy, gastro-resection or prolonged therapy with gastric acidity inhibitor drugs, such as histamine H2 receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors);

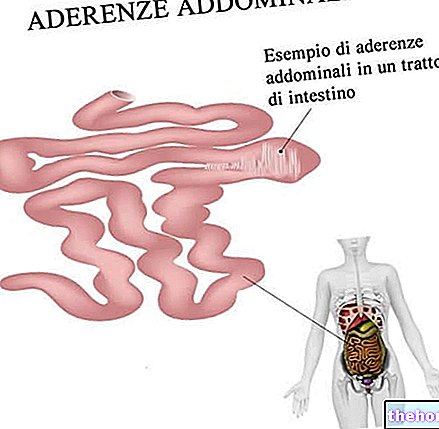

- motor abnormalities that compromise the peristalsis of the small intestine and mechanical factors: systemic sclerosis, diabetic neuropathy, idiopathic intestinal pseudo-obstruction, accelerated gastric emptying, ileocecal valve incontinence;

- anatomical anomalies: gastric atrophy, duodenal and / or jejunal diverticula, stenosis or obstructions, post-surgical alterations (blind loop, intestinal or ileocecal valve resections, jejunoileal bypass).

For many years, bacterial contamination of the small intestine has been recognized as a problem mostly exclusive to major diseases, such as severe intestinal motility deficits. In fact, in recent years new scientific evidence has portrayed SIBO as a rather common disorder, which would affect 30 to 84% of patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). In turn, the symptoms compatible with the clinical picture of IBS are present in 15 to 25% of the population of industrialized countries, with a peak incidence between 15 and 34 years of age and with a frequency approximately double in the female sex compared to to the male sex.

Symptoms: how to recognize bacterial contamination syndrome?

As anticipated, the bacterial contamination syndrome of the small intestine falls into the group of malabsorption syndromes; it can therefore manifest itself with symptoms such as steatorrhea, watery diarrhea, weight loss, discomfort, abdominal distension with flatulence, bloating, cramps and pains, and nutritional and vitamin deficiencies, in particular vitamin B12 (macrocytic anemia). The intensity of the symptoms depends on the degree of bacterial contamination of the small intestine; however, their high specificity leaves numerous diagnostic possibilities open. The signs and symptoms typical of the underlying predisposing pathological condition must obviously be added to the symptomatic process typical of the bacterial contamination syndrome of the small intestine. .

For many decades the gold standard for the diagnosis of bacterial contamination of the small intestine has been the culture of a sample aspirated from the proximal small intestine, a laborious and invasive procedure, now retired from breath tests: after the administration of a known quantity of carbohydrates (typically glucose, lactulose or xylose) the concentration of carbon dioxide or hydrogen in the exhaled air is measured at regular intervals; an early onset peak is an indicator of bacterial fermentation of sugar in the small intestine, with production of gas - including CO2 and H2 - which pass into the blood and are removed from there by breathing.

Drugs and diet therapy

In the presence of a bacterial contamination syndrome of the small intestine it is recommended to adopt a sober diet, characterized by small and frequent meals, not processed, and low in sugar and fat. Considering the heterogeneity of the microbial species that make up the microbial flora intestinal), a broad spectrum antibiotic treatment must be associated with the dietary approach; in this sense rifaximin (Normix, Rifacol) seems to acquire an increasingly important role.

Also important is the possible administration of specific supplements, especially in the presence of weight loss and signs of hypovitaminosis. The underlying causes responsible for the abnormal bacterial growth in the small intestine will then be treated. Antibiotic therapy is sometimes associated or followed by administration of probiotics.