Overall, the result is a reduced ability of the blood to carry oxygen, which results in the characteristic symptoms of anemia (fatigue, weakness, paleness, dizziness, etc.).

Hypochromia has several causes, but is more commonly attributable to iron deficiencies, thalassemia and chronic diseases (such as celiac disease, infections, collagenopathies and neoplasms).

Hypochromia can be diagnosed by having simple blood tests. CBC and evaluation of mean corpuscular volume (MCHC) hemoglobin content are particularly useful for detecting the presence of pale red blood cells.

Treatment involves several approaches, including iron and vitamin C supplements, diet modification, and more or less recurrent blood transfusions. Sometimes, no therapeutic intervention is necessary.

(Hb) lower than normal reference values, for age and sex. The red color of erythrocytes depends on this protein: Hb confers pigmentation in proportion to the volume of the blood cell. Hemoglobin is, in fact, a chromoprotein, that is a protein combined with a colored pigment.

The role of hemoglobin

Hemoglobin (Hb) is a protein contained within red blood cells, specialized in the transport of oxygen to the various parts of the body. In a healthy adult, its concentration should not drop beyond 12 g / dl. "hemoglobin, associated with that of red blood cells in the bloodstream, leads to symptoms that characterize anemia.

Hypochromia: clinical definition

In the laboratory, color can be assessed by measuring "Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin (MCH: is the average amount of oxygen-carrying hemoglobin in red blood cells) and / or Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration (MCHC: is the calculation of the average percentage of hemoglobin inside the red blood cells). Among these two parameters, for the definition of hypochromia the MCHC is considered the best, as it coincides with the concentration of Hb in a single red blood cell, therefore the color indication is related to the size of the cell .

Clinically, in adults, hypochromia is defined by the finding of the following values:

- MCH: below the normal reference range of 27-33 picograms / cells;

- MCHC: Below the normal reference range of 33-36 g / dL.

Hypochromia is often related to the presence of small (microcytic) red blood cells, leading to substantial overlap with the category of microcytic anemia.

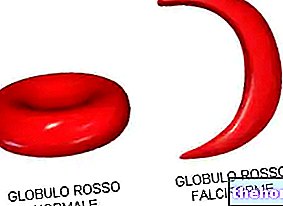

Hypochromia: characteristics of red blood cells

Normally, a red blood cell has a lighter "central area" which, in the event of a decrease in hemoglobin within the same cell, is more extensive.

In the peripheral blood smear followed by microscope observation, in the presence of hypochromia, a diaphanous of the central part of the erythrocytes is evident, which appear of a paler color.

and thalassemia, but hypochromic erythrocytes can also be found in the presence of sideroblastic anemia, inflammatory states and chronic diseases.

The main pathogenetic mechanism of this condition is an "altered synthesis of hemoglobin, as occurs, for example, in thalassemia syndromes due to a deficient synthesis of one or more globin chains.

In some cases, then, the erythrocytes may be clearer due to the presence of genetic mutations that interfere with erythropoiesis, ie in the formation of blood cells; in this case, we speak of hereditary hypochromia.

Hypochromic anemia: what are the main causes?

Hypochromia can be caused by various conditions and diseases, the main ones being:

- Chronic iron deficiencies:

- Low iron intake;

- Decreased iron absorption;

- Excessive iron loss.

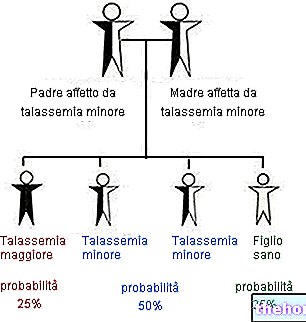

- Thalassemia (hereditary alteration in the blood concerning the chains that make up hemoglobin);

- Inflammations and chronic diseases:

- Chronic inflammatory diseases (eg rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn's disease, etc.);

- Various types of neoplasms and lymphomas;

- Infections (hookworms, tuberculosis, malaria, etc.);

- Diabetes;

- Heart failure;

- COPD;

- Kidney failure;

- Liver disease;

- Hypothyroidism;

- Lead poisoning (substance that causes inhibition of heme synthesis);

- Vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) deficiency;

Less often, hypochromia can occur due to:

- Side effect of some drugs;

- Severe intestinal or stomach bleeding caused by ulcers or other conditions;

- Bleeding from hemorrhoids;

- Copper poisoning.

Rarer forms of hypochromia are congenital sideroblastic anemias (due to deficient heme synthesis) and erythropoietic porphyria.

or it gives a sign of itself only during physical efforts.

Depending on the cause, hypochromic anemia takes on particular characteristics both in symptoms and in the values found with laboratory analyzes.

What are the symptoms of hypochromia?

In general, the manifestations vary according to the severity of the hypochromic anemia and the speed with which it develops. Sometimes, this pathological condition is identified before the onset of symptoms, through simple routine blood tests.

In most cases, hypochromia involves the following manifestations:

- Pallor (accentuated at the level of the face);

- Exercise intolerance, premature fatigue, muscle weakness and fatigue;

- Brittle nails and hair

- Anorexia (lack of appetite);

- Headache;

- Shortness of breath;

- Dizziness;

- Accelerated beats

- Burning in the tongue;

- Dry mouth;

- Abdominal pain

- Painful cramps in the lower limbs during exertion.

Did you know that…

In the past, hypochromic anemia was called "chlorosis" or "green disease" because of the tinge that the skin sometimes took on in patients.

In addition to these symptoms, the following may occur in more severe hypochromic anemia:

- Fainting

- Palpitations;

- Confusion;

- Weak and rapid pulse;

- Wheezing and rapid breathing;

- Chest pain;

- Increased thirst

- Jaundice

- Blood loss and bleeding tendency

- Recurrent attacks of low-grade fever;

- Diarrhea;

- Irritability;

- Amenorrhea;

- Progressive distension of the abdomen (secondary to splenomegaly and hepatomegaly).

For a better characterization of hypochromia, therefore, it is useful to perform the following blood tests:

- Complete blood count:

- Red blood cell count (RBC): erythrocyte count is generally but not necessarily decreased in hypochromic anemia;

- Erythrocyte indices: provide useful information regarding the size of red blood cells (normocytic, microcytic or macrocytic anemias) and the quantity of Hb contained within them (normochromic or hypochromic anemia). The main ones are: Mean Corpuscular Volume (MCV, indicates the average size of red blood cells), Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin (MCH) and Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration (MCHC, coincides with the concentration of hemoglobin in a single red blood cell);

- Count of reticulocytes: quantifies the number of young (immature) red blood cells present in the peripheral blood;

- Platelets, leukocytes and leukocyte formula;

- Hematocrit (Hct): percentage of the total volume of blood made up of red blood cells;

- Amount of hemoglobin (Hb) in the blood;

- Variability in the size of red blood cells (extent of red blood cell distribution, RDW).

- Microscopic examination of the erythrocyte morphology and, more generally, of the peripheral blood smear;

- Sideremia, TIBC and serum ferritin;

- Bilirubin and LDH;

- Inflammation indices, including C reactive protein.

Any abnormalities in these parameters can alert laboratory staff to the presence of abnormalities in red blood cells; the blood sample may be subjected to further testing to identify the cause of the hypochromic anemia. Rarely, a bone marrow sample may be required.

Reduced hemoglobin values and a low hematocrit (percentage of red blood cells in the total blood volume) confirm the suspicion of anemia. By definition, hypochromic anemias are characterized by a mean globular hemoglobin (MCH) content of less than 27 pg and a MCHC below the normal reference range of 33-36 g / dL.

Hypochromic red blood cells are often microcytic, that is, smaller than usual; in this case, we speak of hypochromic microcytic anemia.

If from blood tests, the sideremia is low, the hypochromia probably depends on an iron deficiency or is secondary to a chronic disease.

and some types of sideroblastic anemia are congenital and therefore not curable.

Iron deficiency hypochromia

The iron deficiency form is the condition that is more easily manageable, as it can be dealt with by changing the diet and taking iron supplements orally (or intravenously, when the patient is symptomatic and the clinical picture is severe) and vitamin C (helps to increase the body's ability to absorb iron).

Hypochromia: when it depends on other diseases

When hypochromia is related to other diseases, such as renal insufficiency, hypothyroidism or liver disease, on the other hand, it is necessary to intervene specifically on the primary cause to observe improvements in symptoms.

Hereditary hypochromia

Some types of pathologies, such as thalassemia and some types of sideroblastic anemia, are congenital and hereditary, so there are no treatments available, but supportive measures and symptomatic therapies.

Other therapeutic interventions

When hemoglobin drops to dangerously low levels, blood transfusions can be useful to temporarily increase the oxygen carrying capacity and make up for the shortage of red blood cells. Transfusion therapy can possibly be associated with the intake of chelating drugs, to avoid the accumulation of iron.

The treatment of hypochromic anemia can also include:

- Splenectomy, if the disease causes severe anemia or splenomegaly

- Bone marrow or stem cell transplant from compatible donors.

In addition to specific therapies, regular physical activity and changes in eating habits are of great importance.

In particular, it can be useful:

- Consume foods rich in calcium and vitamin D, due to the risk of osteoporosis (a disease often related to anemia);

- Take folic acid supplements (to increase red blood cell production).

-cosa-significa-quando-preoccuparsi.jpg)