Generality

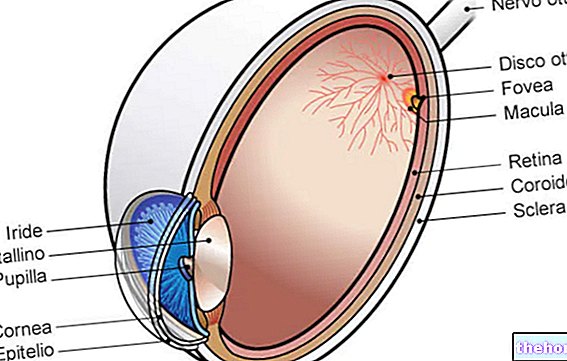

The retina is a tissue of nerve origin, which covers almost the entire inner wall of the eye. This delicate structure contains photoreceptors, which are two types of cells sensitive to light waves: rods are involved in monochromatic vision in dim light conditions or crepuscular; the cones are instead responsible for color vision, but are active only when the light is intense (daytime vision). The retina therefore works as a phototransducer, that is, it captures light stimuli and converts them into bioelectrical signals, which in turn they are sent to the brain through the optic nerve fibers.

In addition to cones and rods, in the retina there are other types of cells (horizontal, bipolar, amacrine and ganglionary), which establish different contacts between them and, overall, contribute to an initial processing of the visual signal.

The retina can be affected by various types of pathological conditions that have different repercussions on vision depending on the area concerned. This structure of the eye can also be affected by vascular or degenerative diseases resulting from general pathologies of the organism, such as hypertension arterial disease, diabetes or vascular sclerosis.

Structure

The retina is the innermost of the three cassocks that make up the wall of the eyeball. Taken as a whole, this membrane is posteriorly grafted onto the optic nerve stem, while anteriorly grafted onto the pupillary margin of the iris.

Note: the retina arises from an ejection of the diencephalon, to which it remains connected by means of the optic nerve.

In all its extension, the retina is structurally made up of two superimposed sheets: one external in contact with the choroid (pigment epithelium) and the other internal in relation to the vitreous body (sensory retina).

The boundary between these two sheets is a line called ora serrata (in this point, the nerve sheet merges with the pigmented sheet and with the vascular tunic).

The sensory retina is the largest portion, consisting of a system of neurons with laminar organization (9 superimposed layers) and, being equipped with photoreceptors and other neurons, it represents the optic part. The pigment epithelium, on the other hand, has a very simple structure, devoid of nerve cells and insensitive to light.

Layers of the retina

The retina is made up of multiple layers of cells, each with a specific function.

Proceeding from the external surface (applied to the choroid) to the internal portion (applied to the vitreous body), we distinguish:

- Pigmented epithelium: it is the outermost layer, interposed between the basement membrane of the choroid and the first nervous layer of the retina formed by cones and rods. The pigment epithelium is made up of a single layer of epithelial cells containing a dark-colored pigment (fuscina). These elements absorb light, preventing it from spreading (to be clear, they create the conditions of a "dark room"). The epithelium pigmented, it has several other functions: it guarantees the exchange of oxygen and nutrients (glucose, amino acids, etc.) and waste metabolites between the photoreceptors and the choroid; phagocytes the membranes of the outermost discs, ensuring a renewal of the receptor structures and constitutes the blood-retinal barrier, which modulates the exchanges between the blood and the retinal tissues. The pigmented layer of the retina also participates in the metabolism of photoreceptors, storing and releasing vitamin A (retinal) for the renewal of visual pigments (note: without the pigmented epithelium, cones and rods would not be able to regenerate the photopigments).

Curiosity. The pigment epithelium is firmly adherent to the choroid on the external side, but can easily separate from the sensory retina. Therefore, when retinal detachment occurs, it is always the two retinal sheets (internal side) that are involved.

- Photoreceptor layer: consists of the outer and inner segments of rods and cones. In their outer segment, the light stimulus causes a reversible chemical modification of the visual pigment and the creation of an electric potential, which is transmitted to the bipolar cells and, subsequently, to the ganglion cells.

- External limiting: it is a very thin connective membrane located on the border between the receptor portion of the photoreceptors and their nuclei.

- External granular layer: it consists of the cell bodies of cones and rods, with their nuclei and their expansions.

- External plexiform layer: it is the first synaptic zone interposed between the final ends of the photoreceptors (spherules in rods and pedicels in cones) and the dendrites of bipolar cells; horizontal cells and Müler cells are also present in this region. The latter are connective elements that have a nourishing and supporting function.

- Inner granular layer: consists of the cell bodies of bipolar cells; there are also Müller cells, horizontal and amacrine.

- Inner plexiform layer: it is the second synaptic zone that connects bipolar cells and ganglion neurons.

- Ganglion layer: consists of the cell bodies of ganglion (or multipolar) cells; there are also the bodies and the expansions of part of the astrocytes.

- Optical fiber layer: it is represented by the axons of the ganglion cells that are preparing to merge into the optic nerve.

- Internal limiting: it is the boundary line between the nerve sheet of the retina and the vitreous body, constituted by the base surface of the Müller cells, with the interposition of a cementing component.

The layers of the nerve sheet of the retina, which go from the photoreceptors to the ganglion cell layer, are essential to activate vision correctly, as they give rise to the transformation of light impulses in the images that we actually see when opening our eyes. Therefore, their main function is to initiate the visual sensory process.

Vascularization

The retina is fed by two independent vascular beds:

- On the inner side, the central artery system of the retina supplies the ganglion and bipolar cells and the nerve fiber layer through the Müller cells and astrocytes, which envelope the capillaries like a sleeve, since there are no perivasal spaces in the retina. . The central artery of the retina penetrates the eye at the level of the optic disc and divides into 4 branches that go towards the periphery. The waste blood goes, through 4 venous branches, in the direction of the papilla and exits the globe through the central retinal vein.

- On the external side, however, the blood reaches the pigmented epithelium and, through this, the photoreceptors through the chorio-capillary system. Venous drainage occurs thanks to the vorticose veins.

Central and peripheral area

The retina is divided into two areas: a central one (rich in cones) and a peripheral one (where rods prevail).

Two regions are of considerable importance: the macula lutea and the optic disc.

- The optic disc (or papilla of the optic nerve) corresponds to the point where the nerve fibers that originate in the retina converge and make up the optic nerve.

Upon examination of the fundus, this area of the retinal plane appears as a small oval area of whitish color, medially and below the posterior pole of the bulb: from here the myelinated axons are collected as they are about to leave the eye. In the center, the optic disc has a depression, known as a physiological excavation, from which the retinal vessels emerge: the branches of the central artery of the retina, which runs along the axis of the optic nerve, radiate into the pupil, while the venous branches there converge with a corresponding course. The optic disc is a blind spot, being devoid of receptors, so it is insensitive to light.

- The macula is a small elliptical area, located in the posterior part of the retina, lateral to the posterior pole of the bulb. This region has some particular characteristics: it is, in fact, the "retinal area with the highest density of cones, responsible for the so-called" fine vision "(that is, it allows you to read the smallest characters, recognize objects and distinguish colors). "inside the macula, there is a depression, called the fovea. This represents the area of best visual definition, in which the greatest amount of light rays is concentrated and which allows the most distinct and precise vision.

Functions

The retina is the structure of the eyeball used for the uptake of light stimuli coming from the outside and for their transformation into nerve signals to be sent, through the optic nerve, to the cerebral structures responsible for visual interpretation.

From a functional point of view, the retinal layers can be schematically reduced to three:

- Layer of pigment epithelium and photoreceptors;

- Layer of bipolar, horizontal and amacrine cells;

- Ganglion cell layer.

The initial site of the light-nerve impulse conversion process is represented by photoreceptors: when the light radiation reaches the retina, photochemical reactions are activated which convert the information received into electrical impulses to be sent to the retinal neurons (phototransduction). Cones and rods, if exposed to light or dark, in fact, undergo conformational changes, which modulate the release of neurotransmitters (chemical signal). These neurotransmitters perform an excitatory or inhibitory action on the bipolar cells of the retina, which, in turn, transmit graded potentials to the ganglion cells. The axonal extensions of the latter constitute the optic nerve and ensure the conduction of action potentials to the brain structures. of the optical pathways, in response to retinal receptor transduction.

The task of carrying the signal out of the retina to the lateral geniculate body and to the cortical areas of the brain, where the visual information is processed, is the responsibility of the optic nerve.

Amacrine and horizontal cells modulate communication in the retinal nervous tissue (for example, via lateral inhibition).

Diseases of the retina

The retina is affected by numerous pathologies, which affect vision with a different level of severity.

Retinopathies are divided into acquired and hereditary. The former are in turn divided into retinal vascular, inflammatory, degenerative diseases and associated with systemic diseases of the organism (such as diabetes and hypertension).

The most common retinal diseases are:

- Diabetic retinopathy: ocular complication that affects about 80% of people with diabetes mellitus for over 15 years;

- Vascular retinopathy: it is due to alteration of the blood vessels; includes arterial and venous occlusions, hypertensive retinopathy and arteriosclerotic retinopathy.

- Detachment of the Retina: consists in the lifting of the nervous retina (the internal section of the retina) from the pigment epithelium (the outermost part); it can be partial (involving only some sectors of the retina) or total.

In addition, degenerative-senile diseases and retinal tumors (such as retinoblastoma) are possible.

Note. Retinopathies are accumulated by the absence of pain, unless other ocular complications occur. This characteristic depends on the fact that the retina is devoid of receptors sensitive to painful sensations.

To assess the "possible presence of retinopathy, the ophthalmologist first of all carries out the examination of the ocular fundus and, to confirm or deepen the diagnosis, a series of more complex diagnostic tests, such as coherent radiation optical tomography (OCT) and" electroretinogram.

.jpg)