- At least in early childhood it is advisable to ensure a molar ratio of Ca / P in the diet of 0.9-1.7 (the two quantities in grams correspond); for an adequate absorption it is however advisable to keep this ratio low because calcium phosphate at intestinal pH is not soluble;

- Deficiency and intoxication syndromes are rare for both, with the exception of premature babies for whom mother's milk is too poor in these minerals;

- Calcemia is normally 9-11 mg / dl, phosphatemia (which is actually less controlled, as it varies even by 1 mg, when calcium has variations of less than 1% over the course of 24 hours) 2.5-4.5 mg / dl; this 2: 1 ratio is fairly constant, again to avoid insolubility phenomena.

Their function is structural, but these quantities can help keep plasma levels constant, thanks to the work of two types of cells, osteoblasts and osteoclasts, which continuously reabsorb and redeploy the bone.

This process allows not only to adapt the bone to any new types of load, but also to mobilize these minerals; to get an idea of its entity, suffice it to say that the entire skeleton of an adult is renewed in 6.5 years, that of a child in one. Of course, if the osteoblastic process is not exactly equivalent to the osteoclastic one, there are variations. Physiologically, calcium in the bones increases up to the second decade of life when, if the conditions have been optimal, the peak mass is recorded bone, genetically determined. After the age of 40, with considerable acceleration after menopause, there is a decrease, mainly due to the decrease in estrogen. This phenomenon, if one remains within the physiological limits, is called osteoatrophy. Osteoporosis is instead, according to the WHO definition, the pathological condition in which bone density or mineral content is less than more than 2.5 SD than the mean value of a young adult; it is a multifactorial disease ial that can also affect young subjects forced to long periods of immobility.

Calcium is present in both interstitial fluids and cells. In the plasma there is:

- 40% in non-diffusible form, bound to proteins;

- for 50% ionized;

- 10% bound to organic and inorganic acids.

In the intercellular fluid it is present only in ionized form. At these levels it is important as a cofactor in coagulation and in regulating the permeability of plasma membranes to Na +, therefore in excitability. Its correct distribution between the two sides of the membranes is essential for the release of histamine, neurotransmitters and hormones and for chemotaxis. In cells it is 90-99% intramitochondrial, thanks to two pumps, one of which, by carrying out a counter-transport of H +, it helps to keep the pH stable (and therefore, consequently, also the concentration of sodium, magnesium, phosphate and bicarbonate) In the cytoplasm it maintains the pH also thanks to its reaction, which is reversible and frees H + with phosphate; it also plays a decisive role in muscle contraction, acts as a second and third messenger.

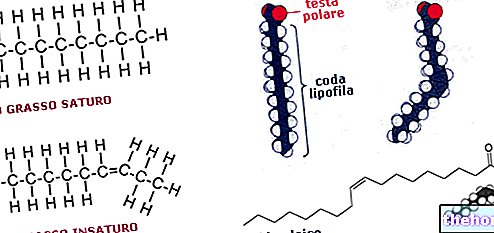

Extraosseous phosphorus is 15% of the total. In plasma it is 85-90% in the form of mono and bi-valent cations, the rest is bound to proteins; it contributes to the acid-base balance. In cells it is fundamental in the processes of phosphorylation of enzymes (activation or deactivation), as a component of nucleic acids and high-energy compounds, membrane phospholipids (70% of total extraosseous phosphorus), proteins and polysaccharides (eg glycogen ).

, eggs (especially in the yolk), milk and dairy products; to a lesser extent and in a less absorbable form in legumes, cereals and vegetables. However, the relationship between the two is different because calcium prevails in milk and dairy products, phosphorus in meat, fish and cereals.

For further information: Calcium and Phosphorus: Needs, Deficiencies, Excess and Metabolism