Edited by Doctor Roberto Uliano

The causes of the yo-yo effect: adipose-specific thermogenesis

Yo-yo effect

In a dietary program there is a rapid decrease in body weight and a subsequent phase of very slow, almost exhausting weight loss. This second phase is very critical for any weight loss program, as the patient gets tired of not getting results and, defeated, resumes his usual diet, sometimes even excessively, regaining the lost weight very quickly.

Slowed metabolism

During a weight loss diet, the body's metabolism decreases

Regardless of the psychological factors that lead to break a diet and resume the previous diet, few people know that, during the phases of food restriction, the organism adapts and changes its metabolic efficiency, also trying to save energy through a decrease. basal metabolism, cellular energy, and the speed of tissue reconstruction. It is as if the body slowed down all its activities to save money and not to succumb to the lack of food.

In 1950 Keys and his collaborators (to be clear the Mediterranean diet scholar) studied the effects of prolonged semi-fasting and subsequent re-feeding on conscientious objectors during World War II. They noted that in the refeeding phase, when body fat was 100% recovered, lean mass recovery was still 40%. These results led to the "preferential accumulation of fat" being described as "post-fasting obesity".

Fifty years later these results were also confirmed by Weyer in anorexia and hypermetabolic pathologies. The slow recovery of lean mass was due either to an inadequate intake of proteins or other necessary nutrients, or to a quantity of food consumed energetically in excess of the body's demands. In fact, it was seen that this mechanism recurred promptly even with balanced diets, with the right amount of protein or low-fat diets.This experimental evidence leads us to understand that there is one slip of the organism towards greater metabolic efficiency in the moments of restriction which allows, however, the subsequent recovery of fat, at the expense of lean mass, in the re-nutrition phase. What is the cause? it is adaptive thermogenesis that plays a crucial role in this mechanism.

Adaptive thermogenesis

Adaptive thermogenesis is a mechanism that allows the production of heat in response to various environmental stresses such as cold, overeating and infections.

In the case of intense cold, the heat serves to keep the temperature of the organs constant, while in the case of hyperalimentation this dissipation of energy serves as a regulator of body weight.

Thermogenesis is under control of the sympathetic nervous system thanks to norepinephrine and thyroid hormones. For further information: brown adipose tissue.

What happens, then, in the restriction phase and in the subsequent re-feeding phase?

Until recently it was thought that the slowdown in weight loss during a diet was due to the loss of lean mass and therefore to the slowdown of the metabolism.

In fact, the slowdown in metabolism is proportional to the loss of lean mass, so losing weight makes it natural to have a lower metabolism. The difference lies in the suppression of adaptive thermogenesis.

In the state of semi-fasting characteristic of low-calorie diets, the body adapts by decreasing thermogenesis, thus eliminating that source of energy expenditure that allows greater weight loss (it often happens that in diets you feel cold).

The consequence is that the weight loss stops.

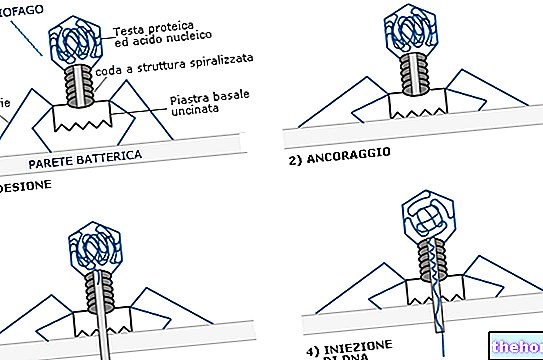

Subsequently, during the re-feeding phase, thermogenesis under the control of the sympathetic nervous system is quickly reactivated to produce heat, so that the organs respond quickly to stressful stimuli, however another type of thermogenesis, characteristic of the muscle, is still suppressed. skeletal, defined as adipose-specific thermogenesis, which depends on the reserves of adipose tissue.

This thermogenesis is a signal sent to the muscle in order not to activate the synthesis of proteins (an energetically very expensive process) and therefore slow down the reconstitution of lean mass.

The downside is that the metabolism still remains in the semi-fast stage and therefore still inefficient to support excessive re-nutrition. Only when the fat reserves are 100% recovered does muscle rebuilding and protein synthesis begin. This means. which increases the likelihood of regaining the lost pounds and beyond.

Furthermore, in this phase there is a higher incidence of hypertensive risk and insulin resistance states, characteristic of diabetes.

The topic still has many points to be explored, but it certainly lays the foundations for a different approach with respect to highly low-calorie diets, an approach that reviews both the metabolic and the nutritional aspects in the therapy of obesity.

Bibliography: Dulloo et al. International Journal of Obesity 2001 522-529