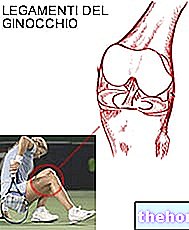

Ligaments: Structures and Functions

Ligaments are strong fibrous structures that connect two bones or two parts of the same bone together. In the human body, there are also ligaments that stabilize specific organs such as the uterus or liver. These important anatomical formations are absolutely not to be confused with tendons, which connect muscles to bones or other insertion structures.

Like the tendons, the ligaments are also formed by type I collagen fibers which have a great resistance to the forces applied in traction. Their elasticity is instead reduced: in the knee, for example, the medial collateral ligament has a resistance to rupture of 276 kg / cm2 but can only deform up to 19% before breaking.It is also a particularly elastic ligament given that on average these important anatomical structures tear if subjected to an elongation that exceeds 6% of their initial length.

However, the elasticity of the ligaments can increase thanks to specific stretching exercises; otherwise the extraordinary degree of joint mobility achieved by contortionists would not be explained. However, it must be considered that such a level of elasticity is as dangerous as excessive stiffness since it significantly increases the degree of joint mobility. "instability and joint laxity.

Ligamentous injuries occur when the forces applied to the ligaments exceed their maximum strength.

The ligaments are all the more susceptible to injury the faster a force is applied to them. If the trauma is relatively slow, their resistance is such as to detach the small part of bone to which they are connected (bone avulsion).

Ankle sprain is a classic example of a ligament injury: when we place a foot badly, the ankle is abruptly moved away from the heel, causing injury to the ligaments that hold these two bones together.

Injuries of the Ligaments

Like a rope formed by the intertwining of many fibers that frays little by little, even the ligaments, if subjected to excessive tension, first stretch, then tear little by little until they are completely ruptured.

The extent of the injury is obviously proportional to that of the trauma and can be classified into three stages of severity:

FIRST DEGREE LESION: inside the ligament only a very small part of fibers is injured; these are microscopic lesions that in the vast majority of cases do not interfere with the normal stability of the joint

SECOND DEGREE LESION: in this case the torn fibers are many more and can remain under 50% of the total (mild II degree lesion) or exceed it (severe II degree lesion). The more collagen fibers are damaged, the greater the degree of instability of the joint

THIRD DEGREE LESION: in this case there is a complete rupture of the ligament which can occur in the central area with separation of the two stumps or at the level of the ligamentous insertion in the bone. In the latter case, a detachment of the bone fragment to which the ligament is anchored may also occur.

SYMPTOMS

Joint instability is the most serious consequence of ligamentous lesions and is directly proportional to the number of torn fibers. Also instability can be classified into different degrees and can be easily appreciated by the doctor through some tests (shift test; anterior drawer test etc.).

Often the ligament tear causes bleeding into the joint space causing swelling, bruising and tenderness around the joint. Pain can also be evoked or accentuated by particular movements. Obviously in most cases (but not all) the symptoms are related to the extent of the lesion and increase in proportion to the number of torn fibers.

Diagnosis is initially clinical, through specific tests, physical examination and investigations on the damaging mechanism and the immediate consequences. The most accurate instrumental investigation is magnetic resonance imaging, which is used only in the most severe cases to confirm the clinical diagnosis. A normal radiograph can be done if associated bone fractures are suspected.

In the acute phase of trauma, the usual and effective RICE protocol is applied: rest, ice, elevation and compression in case of bleeding. Usually, ligament ruptures are treated conservatively and surgery is used only in particular situations.

TREATMENT AND HEALING: fortunately the ligaments are quite vascularized and as such have a good reparative capacity. In the vicinity of the injury, inflammatory cells initially develop which remove dead tissue, preparing the ligament for healing. Subsequently, thanks to an increased local blood flow, a repair tissue is synthesized which, however, needs many months to consolidate and acquire optimal resistance. Generally after a couple of weeks / 3 months, depending on the extent of the lesion, this tissue acquires a resistance that allows the resumption of local strengthening exercises.

In the event of a ligament injury, rehabilitation is extremely important. By applying appropriate mechanical stresses to the ligaments, the correct alignment of the new collagen fibers is promoted (the new fibrils, to offer the right resistance, must align themselves as much as possible in the direction along which the traction forces are applied).

However, early mobilization exercises should not interfere with the healing processes of the traumatized ligament. Also for this reason, in the initial stages of recovery, braces are often used to protect the joint by limiting its mobility.

A ligamentous lesion usually requires quite long recovery times ranging from 4-6 weeks for moderate lesions to 6 or more months for complete ruptures treated with surgery.