Numerous organs participate in digestion, which together make up a long tube called the digestive system. Along this duct, which communicates with the outside through the mouth and anus, numerous anatomical structures can be found, each with a specific role that we will examine in the course of this article.

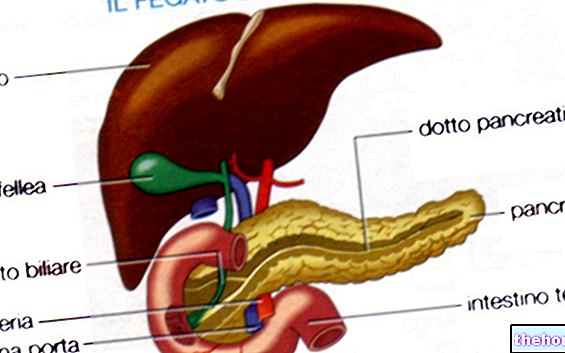

The digestive process, in short, involves: mouth, esophagus, stomach, duodenum and intestine, and digestive enzymes produced by the pancreas and liver.

and to the chemistry of salivary enzymes, foods begin to undergo the first important transformations. The pieces of food crushed and amalgamated with salivary liquids are called a food bolus.

This apparently simple process actually involves numerous structures. Let's think, for example, of the masticatory muscles, their respective innervations, the mechanical action of the tongue and the numerous enzymes contained in saliva.

Among these plays a role of primary importance the ptyalin, an enzyme that favors the digestion of starch. This important complex carbohydrate contained above all in cereals and potatoes is constituted by the union of many simple sugars. To appreciate the digestive efficacy of ptyalin, just chew a piece of bread for a few minutes without swallowing it. As time passes, the bolus will take on an increasingly sweet taste, reflecting the splitting of the long chains of polysaccharides into simple sugars.

Another substance contained in saliva, called mucin, has instead the task of making the food bolus viscous and lubricated.

Proper chewing is therefore the basis for good digestion.

, a process that conveys the bolus inside the esophagus while preventing it from flowing back into the respiratory canal. This mechanism can only take place thanks to the coordinated action of the tongue, larynx and pharynx.

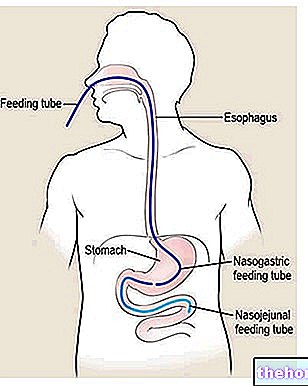

Protected by the sternum and located below the trachea, the esophagus is made up of a dilatable tissue that widens and shrinks based on the presence or absence of a food bolus. This important anatomical structure, similar to a canal approximately 25 centimeters, its function is to put the oral cavity in communication with the stomach.

Inside the esophagus, the bolus is pushed down by a fine muscle contraction mechanism. This function is linked to the presence of a series of muscle rings that contract and relax to allow the advancement of food (esophageal peristalsis). The mechanism is involuntary but so effective as to act even against gravity as when lying on the head down.

The esophagus also has very small glands that pour their secretion into a main excretory duct responsible for fluidizing the esophageal walls. In this way, the passage of food is further facilitated.

Regurgitation of gastric contents is prevented by the presence of a valve located at the lower end of the esophagus. This flap of muscle tissue called the lower esophageal sphincter normally allows bolus to pass in one direction. As soon as the mixture of food and saliva reaches this area, the valve opens, lets the bolus pass, and closes again.

Insights

- Stomach and digestion

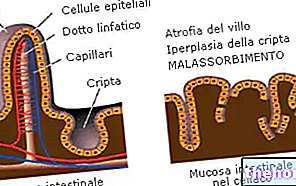

- Small intestine and digestion

- Poor digestion, dyspepsia

- Protein digestion

- Digestion of carbohydrates

- Digestion of fats

- Plants and digestive extracts

- Digestive system

- Digestion times

- Digestive enzymes

- Pancreatic juice

- Gastric juice