Edited by Dr. Giovanni Chetta

Respiratory re-education

Place the palm of your hand on the abdomen, inhale normally, does your hand move forward? Exhale, does your hand, together with the abdomen, return? Now take a deep breath and check the same mechanism. If you answered no to all of the questions, it is very likely that you are breathing incorrectly.

During physiological breathing, in a state of rest (about 15 breaths per minute), it is only in the inspiratory phase that the muscles are used, while exhalation occurs passively (for this reason the inspiratory muscles are more developed than the expiratory ones); diaphragm, as the main inspiratory muscle, should perform at least 2/3 of the respiratory work (abdominal or diaphragmatic breathing): in the respiratory pause the diaphragmatic muscle fibers run almost perpendicularly towards its central area (phrenic center or tendon), during inspiration the muscle fibers contract by lowering the tendon lamina, flattening it, thus increasing the lung volume (elevation of the ribs in lower detail).

As physical effort increases, the activity of the accessory respiratory muscles physiologically increases, which have the task of raising the rib cage by increasing its volume (rib breathing). In the first place the scalene muscles are involved as well as the pair of rhomboid-large dentate or serratus anterior muscles and then, by fixation of the scapula, the pectoral minor, by fixation of the upper limb, pectoral and grand dorsal or latissimus dorsi (which raises the last 4 ribs). As inspiration becomes more forced, the muscles involved will be more and more involved (supra-sottoiodei, sternocleidomastoid, subclavian, ileocostal of the neck, trapezius, levator scapula, elevators of the ribs, inferior dentate, etc.).

In the "active (forced) exhalation, mainly the abdominal muscles (in particular the transverse muscles) are involved.

Anatomically, the diaphragm is a muscle-tendon lamina that divides the thoracic cavity from the abdominal cavity. The diaphragm arches superiorly into the thoracic cavity forming a right and a left dome. The right dome, being in inferior relationship with the liver, is displaced superiorly with respect to the left under which the stomach and spleen are located, very mobile organs. It is made up of a peripheral muscular part and a central tendon part, phrenic center or tendon. The diaphragm can be divided, based on the points of insertion of the muscles that branch off from the tendon center, into three portions: sternal (small muscle bundle connected with the posterior aspect of the ensiform process of the sternum), costal (muscle digitations inserted on the internal face of the last six ribs) and lumbar. This last vertebral muscular portion presents posteriorly two voluminous fibrous bundles of different lengths. The right pillar, longer, is inserted on the cartilaginous discs present between the first, second and third lumbar vertebrae (L1-L2, L2-L3) and sometimes also on the one present between the third and fourth (L3-L4). The left pillar fits on the cartilaginous disc present between the first two lumbar vertebrae (L1-L2) and sometimes on the one present between the second and third (L2) -L3). Lateral to them there are the arch of the psoas which allows the passage of the psoas muscle and the arch of the square of the loins through which the muscle of the same name passes.

The diaphragm relates to important organs. The superior fascia adheres intimately to the heart, whose pericardium is connected through the brake-pericardial ligaments. At the costal level it is in contact with the pulmonary pleural sac. Inferiorly it is largely covered by the peritoneum (which adheres to the phrenic center) and is connected to the liver, via the sickle-cell and coronary ligaments and the right and left triangular ligaments, while the stomach is suspended to it by means of the gastrophrenic ligament and the duodenum via the ligament of Treiz. The spleen is connected to the diaphragm via the brake-splenic ligament, the colon (left corner) via the brake-colic ligament. Posteriorly it connects to the adrenal glands, the upper extremities of the kidneys and the pancreas. The diaphragm also has orifices through which the aorta pass, together with the thoracic duct and the splanchnic nerves (aortic-diaphragmatic canal), the esophagus (esophageal hole) and the inferior vena cava (quadrilateral orifice).

The diaphragm is an involuntary muscle, innervated by the phrenic nerve (the longest and most important branch of the brachial plexus originating at the level of the 4th cervical vertebra), but its activity can also be modified voluntarily.

The modern lifestyle, subjected to unnatural psychological and physical stress (including stomatognathic problems), leads to incorrect breathing. In particular, the majority of the so-called civilized population today perform one rib breathing with shortage of exhalation, accelerated, superficial and often oral. In practice there is almost permanent inspiration, with the diaphragm approximately fixed in the lowered position, with consequent retraction (due to scarce and inadequate use) and alteration of the accessory respiratory muscles (due to excessive and inadequate use). In particular, in the case of an inspiratory diaphragmatic block, given its insertions at the vertebral level, there will be a tendency to lumbar hyperlordosis.

A diaphragmatic dysfunction is able to trigger a vicious circle that leads to further psycho-physical stress, able to facilitate anxiogenic alterations and postural alterations with consequent musculoskeletal problems and, given the close relationship with important organs, organic: respiratory problems ( asthma, false emphysema, etc.), problems with the digestive system (hiatal hernia, digestive difficulties, constipation), dysfunctions related to speech (the diaphragm being the main muscle pushing the air column towards the larynx), gynecological problems (for the diaphragmatic-perineal correlation) and childbirth (the diaphragm is the "engine" of childbirth), circulatory difficulties (the diaphragm plays a fundamental role as a pump for the return circulation through the action of pressure-depression on the thoracic and abdominal organs ).

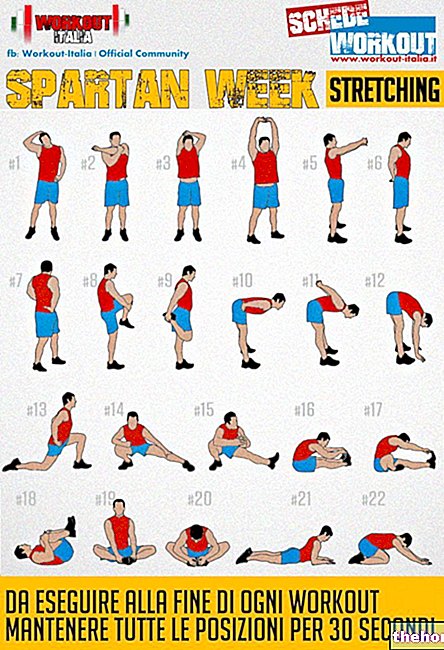

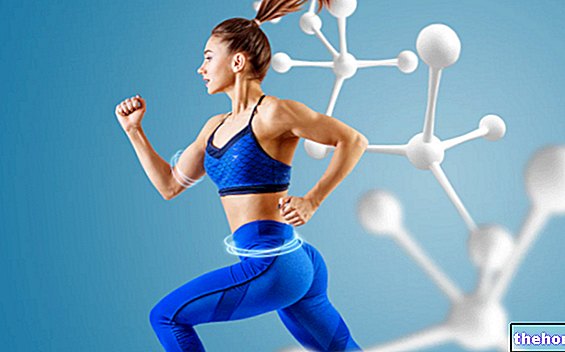

It is scientifically recognized that abdominal breathing represents an excellent prevention against chronic respiratory diseases and pneumonia. Respiratory rehabilitation techniques are used in corrective gymnastics, with the aim of eliminating spoiled attitudes and paramorphisms, and in psychic therapies, in order to arouse liberating emotional breakouts and fight anxiety. respiratory system, to improve the metabolic and circulatory processes of the whole organism, to obtain a better posture, to prevent the onset of anxiety states through a greater control of emotionality and stress, a greater ability to concentrate and relax.

In essence, it is a question of re-learning to breathe like a child (it is for this reason that children, like "little tenors", are able to scream for hours without getting tired). The restoration of correct diaphragmatic function, through appropriate respiratory re-education and possibly specific manual treatments, is therefore of great importance for psycho-physical health. Each respiratory re-education exercise must start from an awareness of one's breathing. It will then be a question of adding a new, more physiological, neuroassociative respiratory conditioning to any incorrect respiratory neuroassociative conditioning; this requires technique and constancy.

During the entire session of postural gymnastics TIB attention is paid to the breathing modality both from the point of view of awareness and re-educational training.

Other articles on "Respiratory re-education - postural gymnastics T.I.B. -"

- Postural gymnastics T.I.B. - gymnastics of maximum effectiveness for the man of today

- Postural gymnastics T.I.B.

- The connective tensegrity network - postural gymnastics T.I.B. -

- The power of relaxation - postural gymnastics T.I.B. -

- Posture and movement - postural gymnastics T.I.B. -

- Postural and posture gymnastics

- "Artificial" habitat and lifestyle - postural gymnastics T.I.B. -

- Postural re-education T.I.B. -

- Maximum efficiency gymnastics - postural gymnastics T.I.B. -

- Motor re-education - postural gymnastics T.I.B. -

- Postural gymnastics T.I.B. - Resistance and Elasticity -

- neuroassociative conditioning - postural gymnastics T.I.B. -

- Physical advice - postural gymnastics T.I.B. -

- Postural gymnastics T.I.B. - Bibliography -

-cos-e-perch-si-esegue.jpg)