Hyperhidrosis

In the skin we find three types of glands: sweat, apocrine and sebaceous ones.

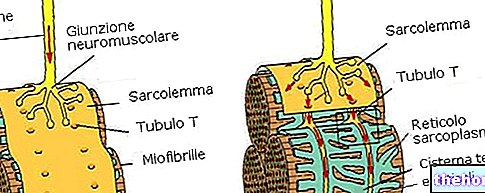

Each sweat gland sinks down to the hypodermis and includes a convoluted part, which represents the secreting unit, and a ductal portion, which opens onto the body surface through a pore (excretory duct).

In the convoluted part of the gland there is a primary secretion of sweat, which takes on a composition very similar to that of the plasma, except for the protein fraction (practically absent in sweat). The rich vascularization of the gland serves precisely to ensure the right supply of the substances necessary for the production of this liquid.

When the primary secretion passes through the excretory duct, most of the electrolytes are reabsorbed (in particular sodium and chlorine) and together with them a certain amount of water, which follows the flow for osmotic reasons. The extent of reabsorption depends on the speed of secretion of the gland. If the production of sweat is slow (poor sweating) the reabsorption is greater, on the contrary, when the flow is rapid the reabsorption is less.

Each of us has about 3 million sweat glands and, unlike many other animals, these glands are distributed over the entire surface of the body, albeit with different densities. Furthermore, their activity is intermittent; each sweat gland alternates periods of quiescence with others of activity. It has been seen that even in the phases of maximum sweating, at least half of these glands are inactive.

The sweat secretion capacity is amazing. Each gland can in fact produce much higher quantities of sweat than its weight. Suffice it to say that, when the temperature rises significantly, an acclimatized body can expel up to 4-6 liters of sweat every 60 minutes.

Sweating power is greater in men, who generally have a more active metabolism and with it a greater need to disperse the heat produced.

Sweat is made up of:

water (99%)

organic and inorganic substances (1%)

Among the organic components there are various nitrogenous compounds (urea, creatinine, uric acid and ammonia). Lactate is also present.

Ammonia, in addition to being part of the composition of fresh sweat, is produced in significant quantities by the bacteria that populate the skin surface. The abundance of this substance contributes to giving an unpleasant odor to the product of the sweat glands.

With sweat various substances (drugs and otherwise) are eliminated, including those contained in particular types of food.

The pH of sweat is slightly acidic, usually between 4 and 6.5. The presence of lactate tends to acidify this liquid, while ammonia shifts the pH towards higher values.

There are three types of sweating: thermal, psychic and pharmacological.

Thermal sweating is induced by an increase in body temperature and is different in the various areas of the body.

Psychic sweating occurs in response to particular moods; it is, for example, induced by anxiety, stress and emotions. The response to these stimuli is subjective, but generally limited to specific areas of the body. Unlike thermal sweating, which it is always accompanied by a dilation of blood vessels, psychic sweating induces vasoconstriction, hence the term "cold sweat", since the skin, due to vasoconstriction, appears pale and cold.

Pharmacological sweating can be induced by various chemical components, derived from catecholamines, antipyretics, antidepressants, but also from some foods and spices.

Finally, there are some particular conditions, such as fever, infections and metabolic imbalances (diabetes, obesity, hyperthyroidism) capable of amplifying the production of sweat.

The main function of the sweat glands is linked to their significant contribution in thermoregulation. Thanks to sweat and skin vasodilation, body temperature can remain relatively constant even in particularly hot environments.

It is very important to keep in mind that sweat alone is not enough to cool the body; in order to have heat dispersion it is necessary for this liquid to evaporate. In fact, sweat, passing from a liquid state to a vapor state, removes heat from the body. In particular, 0.58 kcal are removed from the organism for one gram of water that evaporates from the body surface.

Ambient humidity hinders the evaporation of sweat and this explains the state of discomfort perceived when you are in hot humid environments.

Excessive sweating in a short time involves the risk of dehydration and excessive loss of salts (NaCl).

Problems related to sweating

The most serious is heat stroke, which can arise when the individual is exposed to particularly high temperatures, associated with a high level of humidity. This situation hinders the skin evaporation of sweat, considerably increasing the internal temperature. As a result, the body overheats and the hypothalamic center itself that regulates the time dispersion goes haywire. The consequences can be very serious, so much so that, if you do not take action to cool the body immediately, perhaps with an ice bath, the risk of mortality is quite high. This risk increases during the practice of heavy physical activities, both work and sports The subjects most at risk are children, the elderly and heart patients.

A second problem, less serious than the previous one, is heat collapse. It is essentially caused by an excess of sweating which, due to the consequent dehydration, decreases the mass of circulating blood. In turn this condition, called hypovolemia, causes the appearance of symptoms such as weakness, dizziness, hypotension and, in cases extremes, shock and cardiovascular collapse.

The collapse from heat can be overcome with the simple and gradual reintegration of lost liquids, possibly placing the subject in a cool and shady place.

Other functions of the sweat glands

Sweat enters the composition of the hydrolipidic film, that thin liquid film that protects the epidermis.

In addition to repelling bacterial aggressions, thanks to its acid pH which opposes the skin colonization of numerous microorganisms, sweat contains antibodies (IgA, IgG, IgE), which increase its defensive action against external aggressions.

Finally, the sweat glands also perform an excretory function, which is however moderate, especially when compared with that of the main excretory organs of the organism (kidneys).

the apocrine glands "

.jpg)