NSAIDs and inflammation - Inflammation and the immune system

By inflammation or phlogosis we mean the set of modifications that occur in a district of the organism affected by damage of such intensity as not to affect the vitality of all the cells in that district. The damage is caused by: physical agents (trauma, heat), chemical agents (acids, etc.), toxic agents and biological agents (bacteria, viruses, etc.). The response to damage is given by the cells that have survived the action of it. Inflammation is a predominantly local reaction.

The most important symptoms of inflammation (cardinal) are the heat (local temperature increase due to increased vascularization), tumor (swelling caused by the formation of exudate), rubor (redness linked to "active hyperemia), pain (soreness caused by the compression and intense stimulation of the sensory endings by the inflammatory agent and the components of the exudate) and functio laesa (functional impairment of the affected area).

In addition to acute inflammation due to the abrupt onset and rapid resolution or even angiophlogosis due to the prevalence of the aforementioned vascular-haematic phenomena, there is also the chronic inflammation of longer duration called histophlogosis due to the clear prevalence of tissue phenomena, caused by migration in the tissues of blood mononuclear cells (monocytes and lymphocytes), on vascular-blood cells which in this case may also be completely absent. This is a simplistic schematization, useful under the didactic aspect, as acute inflammation is not always it is short-lived. Chronic inflammation may follow or be acute inflammation from the start. Under the etiological aspect it has long been known that some agents selectively induce a chronic inflammatory response, but only recently has it been shown that the "one or the other type of response is triggered under the pathogenetic aspect by the preferential release of two specific categories of cytokines: type I (or TH1) and type 2 (or TH 2).

Angiophlogosis

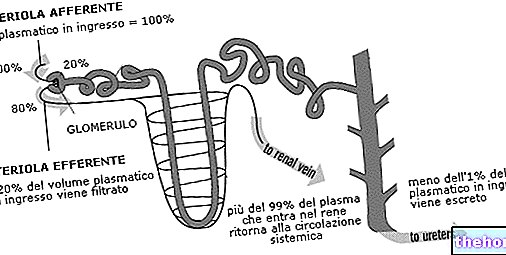

It essentially takes place in correspondence with the microcirculation, that is, the peripheral part of the circulatory system. This is the vascular district that includes the terminal lymphatic network, physiologically responsible for the supply of oxygen and nutritional substances to the tissues and for the removal of carbon dioxide and catabolites. When an inflammatory stimulus hits an "area of any organ, a part of the cells becomes necrosis or is more or less severely damaged with the consequence that the cellular debris that is formed also constitutes" a "further phlogogenic stimulation for the cells that remain unharmed. As a consequence of this, a series of events occur that involve the microcirculation:

- very short duration vasoconstriction (10-20 sec.), mediated by the sympathetic branch of the vegetative nervous system (release of catecholamines); it may also be missing and does not play a significant role.

- vasodilation, caused by the relaxation of the smooth muscle cells present on the wall of the terminal arterioles.

- active hyperemia, depends on the collapse of the precapillary sphincters and the dilation of the arteriolar wall, which allows a greater flow of blood into the microcirculation causing the appearance of calor and rubor symptoms.

- passive hyperemia induced by the slowing of the blood velocity in the microcirculation

- migration (diapedesis) of leukocytes, that is, the leakage of these cells from the blood compartment into the extravascular one where they are recalled by particular cytokines endowed with chemotactic activity called chemokines and by numerous other chemotactic factors.

- formation of the exudate, consisting of a liquid part and the cells suspended in it. The liquid part of the blood escapes from the vessels due to an increase in hydrostatic pressure, due to hyperemia and due to a reduction in colloidosmotic pressure due to the reduced concentration of plasma proteins which accumulate outside the vessels, they contribute to the further attraction of water here. The presence of the exudate determines the formation of the inflammatory edema and is responsible for the tumor symptom.

- phagocytosis of cellular debris and microorganisms by phagocytes which is followed by the resolution or chronicization of the inflammatory process.

The chemical mediators of inflammation

They are represented by numerous molecules that trigger, maintain and even limit the modifications of the microcirculation described above. Some of them are contained in cellular organelles from where they are released only if the cells are reached by inflammatory stimuli (preformed mediators), others are synthesized and secreted following gene derepression triggered by inflammatory stimuli (newly synthesized mediators) and others are formed in the blood from inactive precursors (fluid phase mediators).

Numerous cells accumulate in the inflammatory focus performing various functions among which the main ones are:

- they contribute with the production of cytokines and other chemical mediators to the genesis, maintenance, modulation and, finally, to the resolution of the inflammatory process;

- they contribute directly to the elimination of many phlogogenic agents through the phagocytosis process;

- they represent the point of interconnection between the inflammatory focus and the body's immune response.

The cells involved in the inflammatory process are mast cells, basophilic granulocytes, neutrophil granulocytes, eosinophilic granulocytes, monocytes / macrophages, NK cells, platelets, lymphocytes, plasma cells, endotheliocytes, fibroblasts.

The formation of the exudate

As a consequence of the increase in capillary permeability, the increase in hydrostatic pressure and the obstacle to lymphatic drainage, exudate is formed, i.e. passage of the liquid part of the plasma from the vascular to the interstitial compartment which involves a collection of liquid in the "interstitium which is given the name of inflammatory edema. The exudate which has an acidic pH due to the presence of lactic acid, consists of a liquid part and a cellular part. The liquid part derives from plasma and contains proteins, nucleic acids, phospholipids. The cellular part varies in composition depending on the type of exudate and is represented by blood cells of the white series, mainly polymorphonuclear cells that cross the capillary wall by diapedesis. Various types of exudate are distinguished (serous, sero-fibrinous, catarrhal or mucous fibrinous, mucopurulent, purulent, hemorrhagic, necrotic-hemorrhagic, allergic) each characteristic of a specific type of acute inflammation.

Evolution and outcomes of acute inflammation

The outcomes of the inflammatory process can be of three types:

- necrosis, caused by cellular destruction operated by lysosomal enzymes that damage not only microorganisms but also tissues, causing tissue death.

- chronicization, which occurs when the phlogistic reaction has not completely eliminated the phlogogenic agent.

- healing (the liquid part of the exudate is reabsorbed while the leukocytes undergo programmed cell death after engulfing and destroying the phlogogenic agents)

Chronic inflammation or histophlogosis

The chronic inflammation of the inflammatory process, due to the lack of elimination of phlogogenic agents is not the only mode of onset of chronic inflammation as this can be such from the beginning due to:

- certain characteristics of some phlogogenic agents and in particular their resistance to intracellular killing mechanisms;

- the preferential production of type I cytokines.

When an "acute inflammation becomes chronic, first there is a progressive reduction of blood vascular phenomena and the amount of exudate, as also occurs in the healing process, while at the same time the neutrophils are replaced by a cell infiltrate consisting mainly of macrophages, lymphocytes, plasma cells and NK cells that arrange themselves around the vascular wall like a sleeve that induces its compression. As a consequence, a state of tissue suffering occurs. Subsequently, the fibroblasts can be stimulated to proliferate with the consequence that many chronic inflammation culminate in excessive formation of connective tissue which constitutes the so-called fibrosis or sclerosis. Chronic inflammation presents under the clinical aspect in two different forms: non-granulomatous and granulomatous.

In chronic non-granulomatous inflammations the morphological picture, represented by the lymphomonocyte infiltrate, presents with a prevalence of lymphocytes and plasma cells and maintains the same characteristics whatever the etiological agent responsible for the process.

The granulomatous ones intervene when microorganisms of various types survive in the phagolysosomes of macrophages or when their products or even indigestible organic or even inorganic materials remain in these.

Systemic manifestations of inflammation

Even if it is a localized process, the organism is affected by its presence due to the cytokines which, having penetrated into the blood, reach all the organs in correspondence with which they interact with the cells that expose specific receptors for them, stimulating certain functions. There are three phlogosis: leukocytosis (increase in leukocytes in the blood), fever and the acute phase response (modification of the cellular component of the blood, which undergoes changes in its protein content).

Generally speaking, it can be said that neutrophilic leukocytosis characterizes angiophlogosis while lymphomonocyte leukocytosis is typical of histophlogosis.

The reparative process

It has the task of ensuring the formation of a cell continuity that fills the void formed as a result of the injurious event by stimulating the proliferation of the surviving cells present in the injured area. The cells are divided into: labile cells (they multiply continuously), cells stable (they have the potential to replicate), perennial cells (they never reproduce). At the edge of the tissue lesion an acute phlogistic reaction is established thanks to which the injured area is invaded by phagocytes, which destroy cellular debris. Granulation tissue is formed immediately, consisting of endotheliocytes, which form solid cords that gradually lumify, so that the blood can pass through them, and at the same time the fibroblasts that will form the scar proliferate. The stimulus to the proliferation of endotheliocytes and labile and stable cells is given by the release of cytokines by the surviving cells and inflammatory cells.