Definition

We speak of thinness when the body weight falls below 90% of that considered ideal on the basis of age, sex, height, constitution and habitual physical activity.

Still others refer to the BMI or body mass index, which considers all people with a weight / height ratio2 less than 18 to be thin.

Thinness, even when it is very pronounced, is not necessarily synonymous with disease. It is therefore important to establish first of all whether we are dealing with a constitutional thinness or secondary to physiological or pathological causes.

Types of Thinness

As mentioned, when we talk about thinness, this does not necessarily appear to be associated with pathologies, but it could also be constitutional thinness or thinness secondary to physiological causes (due, for example, to an increase in physical activity or to the adoption of a restricted diet).

Therefore, when it comes to reduced body weight it is necessary to make a distinction between constitutional thinness, that is, devoid of pathological significance, and weight loss secondary to disease or malnutrition.

Constitutional leanness is characterized by a marked generalized reduction of fat mass, with a saving of lean mass which is in line with the standards of the long-limbed constitution.

On the other hand, the picture of pathological thinness is quite broad and includes, just to name a few, endocrinopathies, gastrointestinal diseases, chronic infectious diseases, neoplasms, neuropsychic diseases, forced undernutrition and protracted physical stress.

Thinness in athletes

Among the three definitions proposed above, the most suitable in the sports field is undoubtedly the one that refers to the fat mass of the individual, as long as an appropriate distinction is made between man and woman.

Total fat mass can be divided into two components: primary fat and reserve lipids. The first includes the adipose deposits present in the bone marrow, lungs, liver, spleen, kidneys, intestines, muscles and central nervous system. Primary fat does not have a simple energy function, but is biologically essential for support vital functions of primary importance (see: the functions of lipids). For this reason the primary fat reserves represent the minimum amount of body fat compatible with health. In man the primary fat is around 3-4% of the mass total body, while in women, by virtue of the fat reserves necessary to support reproductive functions, this percentage increases up to 12-14%.

Some athletes become amenorrhoeic (less than 3 menstrual cycles per year) already at levels of adipose mass below 16%, with a consistent loss of bone minerals and with an increased risk of fractures and premature osteoporosis. In men when the fat mass falls below 5-6% there is a greater susceptibility to infections.

In reference to an "athlete, we speak of thinness when the percentage of fat mass falls below 5% in men and 15% in women.

Thinness in healthy people

The terms underweight and thin are not necessarily synonymous, nor are the terms overweight and fat. For this reason, the most appropriate definition of thinness when talking about healthy people is the following:

- In reference to a healthy person, we speak of thinness when the body weight falls below 90% of that considered ideal on the basis of age, sex, height, constitution and habitual physical activity.

It is therefore necessary to choose evaluation criteria that allow us to estimate the individual's ideal weight, taking into account the various components that influence it. In the article "the ideal weight" we have proposed this automatic calculator for adults.

When it comes to thinness, it is also important to evaluate the anamnestic history of body weight, since rapid and sudden weight losses are more likely to take on pathological connotations.

Pathological thinness

Unlike athletes and healthy people in whom these components are spared, in pathological thinness, weight loss is often accompanied by a consistent loss of bone and muscle mass. Let's think, for example, of skeletal diseases, characterized by a reduced bone mass (osteoporosis, osteomalacia, bone tumors, etc.). In these conditions, the previously proposed thinness standards may be inadequate.

A first criterion for evaluating the pathological or constitutional origin of thinness is the relationship between appetite and body weight. A constitutionally thin subject subjected to a high-calorie diet shows a notable resistance to gaining weight and, despite overeating, his weight on the contrary, a malnourished individual responds positively to the caloric surplus, gaining weight.

In the presence of pathological thinness, the situation is more complex, since the subject can lose weight both due to a significant loss of appetence, and in the presence of appetite and normal or even increased caloric intake.

Diagnosis

Pathological thinness is the symptom of even very serious basic diseases. For this reason, it is essential to promptly diagnose it, in order to determine the pathology that triggered it as quickly as possible.

Generally speaking, we can say that thinness takes on pathological significance when:

- It suddenly arises in a normal-weight and normal-fed subject;

- Despite dietary therapy, it tends to worsen with the passage of time;

- It is accompanied not only by a reduction in fat mass, but also by loss of muscle tissue and, in some cases, bone demineralization.

Once the pathological thinness has been diagnosed, on the basis of the analysis of the other symptoms presented by the patient, the doctor will then be able to evaluate - with the help of any additional tests - which pathology has affected the patient.

In the case of thinness sustained by eating disorders, however, the picture is more complicated and dictated by an "altered perception of" body image. Anorexia nervosa, in fact, includes a great variety of symptoms ranging from intense physical activity associated with systemic rejection of certain foods, up to the use of elimination behaviors (self-induced vomiting, diuretics, laxatives, etc.) following copious binges .

Causes

The ailments that can cause thinness are many, each of which is accompanied by its own clinical picture.

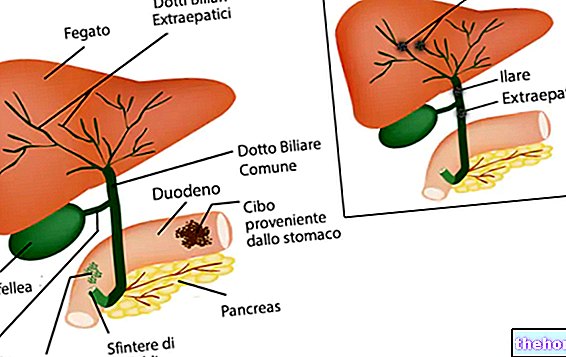

If thinness is accompanied by a reduction in appetite, the triggers could be diseases such as anorexia nervosa or tumors of the gastrointestinal tract and pancreas.

On the contrary, if thinness is associated with a normal appetite or an increase in it, the pathologies responsible for its appearance could be of an endocrine nature (such as, for example, in the case of "hyperthyroidism), pituitary diseases, diabetes mellitus or" drug abuse (for more information: Thinness - Causes and Symptoms).

Treatment

In case of pathological thinness, the therapeutic approach to be employed will depend on the underlying pathology that caused it and on the timeliness with which it is diagnosed.

For this reason, when you notice an "undesirable excessive weight loss and, above all, if it occurs abruptly and suddenly, it is essential to immediately contact your doctor who will take all the necessary measures.

CONTINUE: Diet against constitutional thinness "

.jpg)