Generality

Lipases are water-soluble enzymes that catalyze the digestion of dietary lipids, breaking down the ester bond that binds the hydroxyl groups of glycerol to long-chain fatty acids.

In the absence or lack of lipase, the absorption of fats does not occur correctly and a part of the dietary lipids passes into the faeces causing steatorrhea (abundant emission of pasty excrements, with a shiny and shiny appearance).

Synthesis

Unlike amylases, which are secreted only by the salivary glands in the upper tract of the digestive tract, lipases are released both in the oral cavity and in the gastric cavity.

Furthermore, lingual lipase, which is secreted in the posterior region of the tongue, is active in a broad pH spectrum (2-6) and can therefore continue its activity also in the acid pH of the stomach (unlike ptyalin which works preferentially to pH between 6.7 and 7).

Fat digestion

Gastric and lingual lipases attack triglycerides (which represent about 90-98% of dietary lipids), detaching a fatty acid and thus producing diacylglycerols (glycerol esterified with 2 fatty acids) and free fatty acids. In the two or three hours that food remains in the stomach, oral and gastric lipases are able to break down about 30% of dietary lipids.

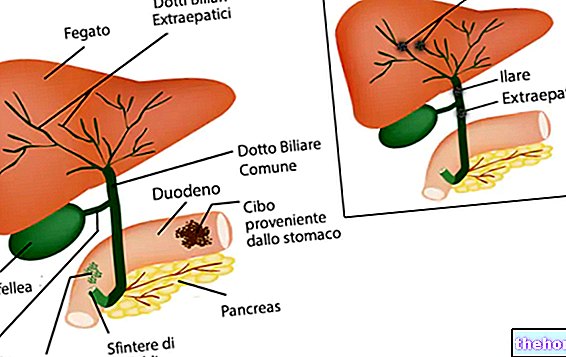

However, the most important source of lipase remains the pancreatic one, which is why the aforementioned steatorrhea is typical of all those conditions that decrease the functionality of the pancreas.

The final products deriving from the action of pancreatic lipase are monoglycerides (2-acylglycerols) and free fatty acids; unlike salivary lipase, which detaches only one fatty acid, in fact, pancreatic lipase can detach both fatty acids from the hydroxyls (carbon 1 and 3) of glycerol The 2-acylglycerol thus obtained spontaneously isomerizes in the alpha form (3-acylglycerol) and can then be attacked again by a lipase which splits it into glycerol plus a free fatty acid.

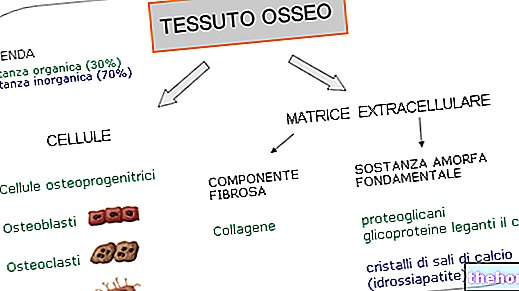

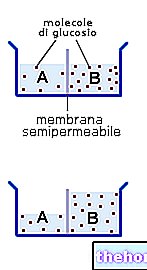

The activity of pancreatic lipases is assisted by colipase enzymes secreted by the pancreas, which favor its adhesion to the droplets of fat. Not only that, in order for an optimal digestion of fats to take place, the intervention of the bile produced by the liver is necessary, which - in synergy with the peristaltic movements - leads to the emulsion of fats, breaking down the lipid aggregates into very fine droplets that are easily attacked by lipase.

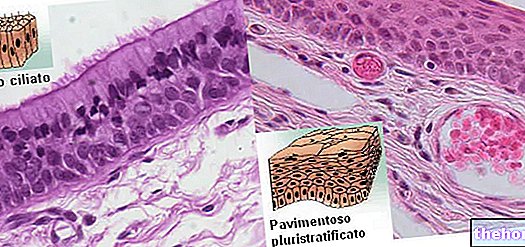

What happens in the small intestine is a fundamental step in the digestive process of fats, since only monoglycerides and free fatty acids can be absorbed by the intestinal mucosa.

For what has been said, it is therefore possible to have steatorrhea even in the presence of liver diseases or large intestinal resections.

In addition to lipase, the pancreas also produces a phospholipase (called phospholipase A2) and a carboxylesterase. The former preferentially removes the fatty acid in position two of the phospholipids, producing free fatty acids and lysophospholipids, while the carboxylesterase breaks down the esters of cholesterol, fat-soluble vitamins, triglycerides, diglycerides and monoglycerides.

Other lipases are produced by the liver, the vascular endothelium and within the cells, such as lysosomal and hormone-dependent lipases.

Absorption and Distribution of Fat

Once absorbed, fatty acids and other digestive products are reconverted into triacylglycerols and aggregated to specific transport proteins, giving rise to small lipoprotein masses called chylomicrons. These are poured into the lymphatic circulation and subsequently into the blood, then transported to the muscle and adipose tissue. In the capillaries of these tissues, the extracellular enzyme lipoprotein-lipase hydrolyzes the triacylglycerols to fatty acids and glycerol, which enter the target cells. In those of the muscle type, the fatty acids are oxidized to produce energy, while in the target cells of the tissue. adipose are reesterified to triacylglycerols to be stored as reserve fat.

High lipases "

.jpg)