«Intestine: physiology and anatomical references

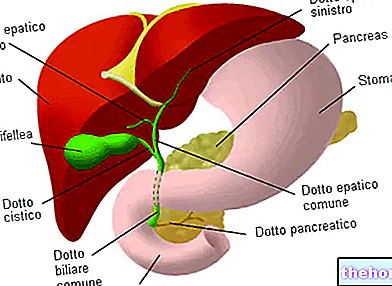

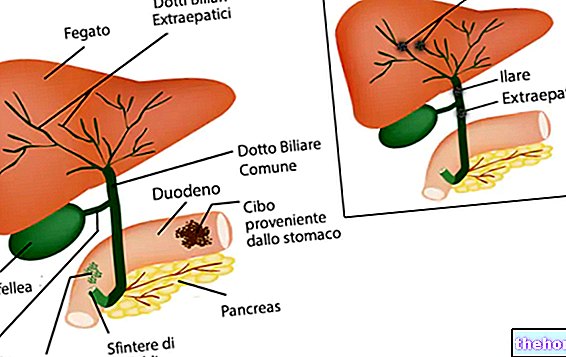

Two important annexed glands (the pancreas and the liver) pour their product into the duodenum, which contribute to the enzymatic digestion of food. The juices that we find in the intestine are therefore three: the pancreatic juice, which obviously comes from the pancreas, the bile, coming from the liver, and the enteric juice which is produced directly from the small intestine.

In the duodenum, the acid chyme from the stomach receives intestinal, hepatic and pancreatic secretions, giving rise to a milky liquid called chilo.

The pancreas has an endocrine portion, responsible for the production of various hormones such as glucagon and insulin, and an exocrine portion, which synthesizes pancreatic juice.

Inside this juice we find many enzymes capable of hydrolyzing most of the nutritional principles. Among these, an important role is played by "pancreatic almylase, an enzyme responsible for the digestion of" starch. The adjective "pancreatic" is used for distinguish it from ptyalin or salivary amylase which, despite the different origin, has the same function.

Pancreatic amylase breaks down the starch present in food into maltose, maltotriose and dextrins (glucose molecules in which a branch remains), completing the work initiated by ptyalin. Unlike what happens in the oral cavity, raw starch is also digested in the intestine, since the cellulose wall that encloses it is damaged during its stay in the stomach.

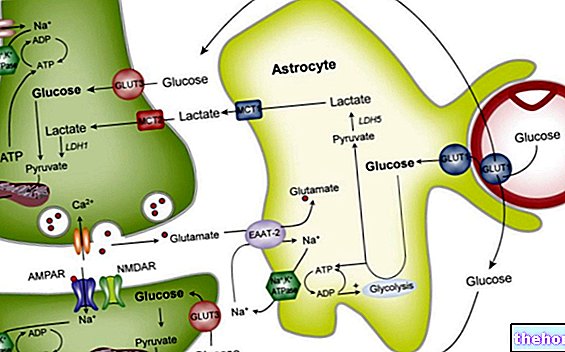

The microvilli contain enzymes that complete the digestion of the various nutritional principles. At this level we find, for example, the sucrase enzyme, which leads to the formation of glucose and fructose starting from a sucrose molecule, the lactase enzyme, which digests milk sugar by breaking it down into a molecule of glucose and one of galactose , and the maltase enzyme, which digests maltose and maltotriose by breaking them down into the individual glucose molecules that compose them.

Finally, in the small intestine there is also an enzyme called dextrinase, capable of digesting dextrins, and a fifth, called nuclease which, together with ribonucleases and pancreatic deoxyribonucleases, digests nucleic acids.

In addition to amylase, the pancreas secretes various enzymes, such as trypsinogen and chymotrypsinogen, which act on proteins already partially digested by gastric pepsin. Similarly to what happens in the stomach, these two enzymes are also secreted in an inactive form and acquire the capacity to digest proteins only after they have been secreted into the intestinal lumen, where they are activated by the enzyme enterokinase.

Trypsin and chymotrypsin continue the activity of gastric pepsin, further reducing the partially hydrolyzed peptides in the stomach. The digestive activity is completed by the enzymes present in the juice, such as dipeptidases, which break down the oligopeptides into the individual amino acids that compose them.

In addition to amylase, trypsin and chymotrypsin, pancreatic juice contains a third enzyme responsible for the digestion of fats. This enzyme is called lipase and its action is assisted by a cofactor, called colipase, secreted by the pancreas as procolipase and activated by trypsin.

Despite these enzymes, the digestion of lipids necessarily requires an "additional substance, secreted by the liver and called bile. The main components of bile are bile salts, essential for emulsifying lipids, and waste products such as cholesterol and bile pigments. These are the main components of bile. substances are secreted in the intestine to be excreted with the faeces and, while the excess cholesterol can only be eliminated via this route, the bile salts can also be excreted through the urine.

A common characteristic of bile and pancreatic juice is the modest basicity, guaranteed by the presence of sodium bicarbonate, which has the task of neutralizing the hydrochloric acid coming from the stomach. Thanks to this buffer system, the intestinal environment is neutral, tending to basic.

Bile is produced by the liver, from which it exits through the hepatic duct to be conveyed to a storage organ called the gallbladder. Between meals, this pouch collects and concentrates bile, introducing it into the duodenum in conjunction with meals.

Pancreatic and biliary secretion is stimulated by numerous gastrointestinal hormones (gastrin, secretin, cholecystokinin, etc.). There is also a nervous control, which stimulates secretion through the vagus (parasympathetic) nerve and inhibits it thanks to the efferent fibers of the orthosympathetic nervous system.

The integrity of the sympathetic pathways, which innervate and stimulate the intestinal smooth muscle, is not essential for the coordinated functioning of the intestine. At this level there is in fact an autonomous nervous system, a sort of "second brain" sensitive to the same chemical stimuli received by the CNS. Its function is not simply digestive, but also immune and psychological, since it is in turn capable of secreting psychoactive substances, captained by serotonin, which influence the activity of the central nervous system. When this brain goes into crisis due to a strong psychophysical stress or due to the presence of poisons or pathogens in the digestive tract, intestinal motility undergoes important changes. If it increases to expel harmful substances, diarrhea occurs, on the contrary when it slows down, due to the increased colonic absorption of water, constipation arises ( to learn more: irritable bowel syndrome).

The hormone cholecystokinin takes its name from its action, gallbladder is in fact synonymous with gallbladder while the term quinine means movement or contraction. This hormone, produced by the intestine in response to fatty and protein meals, stimulates the contraction of the gallbladder , favoring the entry of bile into the intestine.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)