Bolus

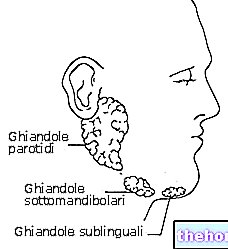

The food bolus is that pulp of food mixed with saliva that forms in the mouth during chewing, thanks to the mechanical activity of the teeth, which compact the tongue and lubricate the saliva. The salivary enzymes, for their part, perform a partial digestion of food , transforming starches into oligosaccharides and dextrins. Each bite is therefore made unrecognizable by the chewing activity which, when particularly prolonged, gives starchy foods a sweetish taste, a sign of their partial digestion with the release of oligosaccharides (which have a moderate sweetening power). The end result of all these processes is a pulp of shredded, chopped and partially digested food, called a bolus.

In the light of all these important modifications, undergone by the foods inside the oral cavity, the bolus is considered the first product of digestion.

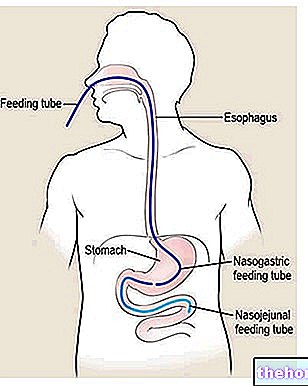

During swallowing, the bolus is pushed towards the pharynx, while a series of involuntary contractions prevent it from rising and falling into the upper and lower airways.

After passing the upper esophageal sphincter, the bolus is channeled into a tube about 24 cm long called the esophagus, which descends pushed by peristaltic contractions until it reaches the gates of the stomach.

Chimo

Once in the stomach, the bolus is kneaded and mixed with digestive acids and enzymes, such as pepsin and gastric lipase. After a period ranging from two to five hours (depending on the quantity and nature of the food ingested), what was once called a bolus has become a brothy and particularly acidic liquid called chyme. It contains digestive enzymes, a certain amount of hydrochloric acid and partially digested food, especially in the protein fraction (pepsin secreted by the stomach is a key enzyme in the digestion of proteins). Hydrochloric acid, for its part, kills most of the ingested microorganisms, facilitates the digestion of proteins and that of raw starch.

Kilo

After gastric digestion, the chyme coming from the stomach is gradually pushed into the first tract of the small intestine, called the duodenum. This passage does not occur abruptly, but in small successive waves, so as not to overload the enteric systems of absorption and digestion.

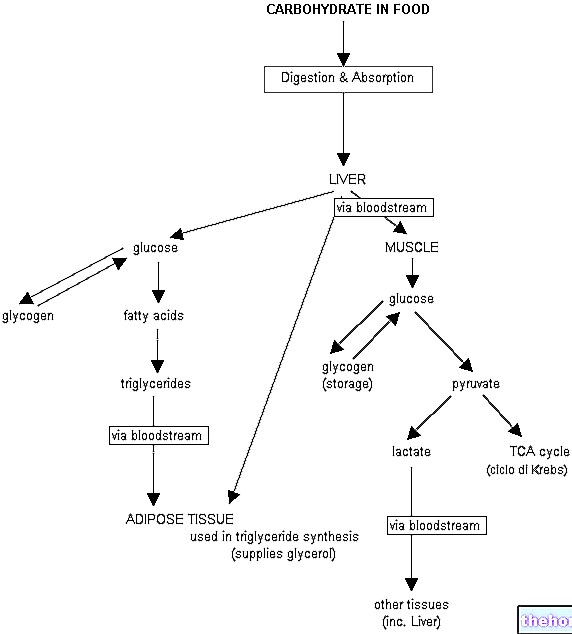

The products of important glands, such as the pancreas (pancreatic juice), liver (bile), and intestinal glands (enteric juice), flow into the duodenum. The kilo, a milky, slightly basic liquid, rich in nutrients and enzymes involved in the final phase of digestion, originates from the mixture between the acid chyme and these secretions.

The enzymatic action ultimately produces elementary nutrients of particularly small size, which allow it to cross the intestinal mucosa and pour into the blood or lymph (where lipids and other fat-soluble components are poured out in the form of chylomicrons) .

Once in the final tract of the small intestine, called the ileum, the kilo is now poor in nutrients, which have been subtracted from the intestinal villi of the duodenum and subsequent tracts of the small intestine (jejunum and ileum).

Leaving the small intestine, the kilo's journey continues towards the large intestine, where it is deprived of water and mineral salts, attacked by the intestinal flora, enriched with mucus and flaking cells, until it is transformed into a waste product called feces. pushed by peristaltic movements, they are accumulated in the fecal ampulla and from here channeled at the right moment into the rectum, which expels them outwards through the anus.