Edited by Prof. Guido M. Filippi

Institute of Human Physiology of the Catholic University of Rome

Professor of Human Physiology of the degree course in Motor Sciences of the Catholic University of Milan

INTRODUCTION

There is a separation, measurable in several decades of research, between the acquisitions of neurophysiology and sports training practices. Neurophysiological research, both for its complexity and for the apparent distance from the problems of the training "field", remains almost extraneous to sports training and its problems.

This does not imply that neurophysiology does not have to say, nor that sports training does not have entirely interesting ideas to offer to basic research.

Even today, most of the training is aimed only at the engine: the muscle. The muscle, in fact, is a real engine, which transforms the chemical energy of the ATP into mechanical energy, as the engine of our car transforms the " chemical energy of hydrocarbon molecules into mechanical energy.

The prevailing interest is therefore for the engine, the muscles, easier to build, but with two flaws: the more they grow, the more the human machine weighs and the need for a driver, the brain.

In reality this is the crucial problem today, in consideration of the levels reached by the competitive spirit.

To further exemplify the problem, consider the pairs of athletes shown in Figure 1; note, how drastically different physicists from a muscle volume point of view can express similar results, or even how the less performing physique can prevail, agonistically, over the bigger one.

It is common experience that higher muscle masses in athletes are not necessarily the expression of better athletic gestures. The speed of execution, the power, the precision of a movement, the resistance appear to depend on something other than the muscle.

The Nervous System is the architect of the management of the available muscles and the oriental martial arts are a concrete expression of how control can be transformed into power.

The purpose of this discussion is to outline:

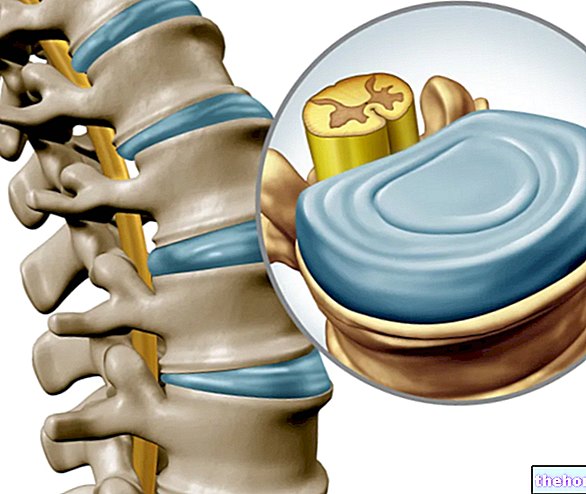

- The role of the nervous system in determining muscle properties and the problem and advantages in optimizing muscle control (part I)

- Today's possibilities to intervene with training directly on muscle management, performed by the Central Nervous System, in order to optimize neuromotor function and obtain superior muscle performance, avoiding, however, any intervention harmful to the health of the athlete, or using only neurophysiological mechanisms (Part II).

PART I.

ROLE OF THE NERVOUS SYSTEM IN DETERMINING MUSCLE PROPERTIES

The assertion according to which muscular work is an essential condition for the development, strengthening and improvement of motor function in general (Figure 2).

This statement is only partially true.

In fact, if it follows from this statement that physical work is the direct responsible for improving motor performance, the statement becomes wrong.

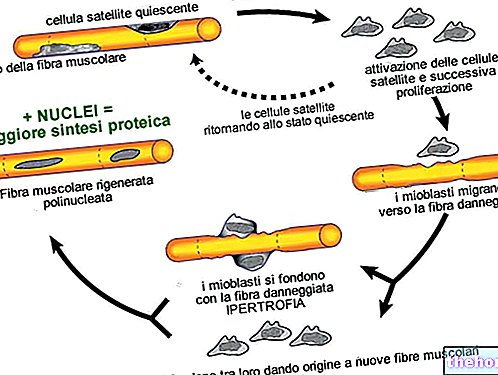

In fact, both the trophism and the metabolic properties of the individual muscle fibers depend on the quantity and distribution over time of the nerve command that reaches the muscle fibers, on average, over the course of 24 hours. Neurophysiological research has demonstrated this since the 1960s (Principles of neural science. Eds Kandel ER, Schwartz JH and Jessell TM. Elsevier NY. 1991).

Other articles on "Neurophysiology and sport"

- Neurophysiology and sport - second part

- Neurophysiology and sport - third part

- Neurophysiology and sport - fourth part

- Neurophysiology and sport - fifth part

- Neurophysiology and sport - sixth part

- Neurophysiology and sport - eighth part

- Neurophysiology and sport - Conclusions

.jpg)