Watch the video

- Watch the video on youtube

Water in the Human Body

Water is a very important nutrient for our organism, so much so that in its absence death occurs within a few days.

In fact, water performs innumerable and vital functions:

It is an excellent solvent for many chemicals;

regulates cell volume and body temperature;

promotes digestive processes;

allows the transport of nutrients and the removal of metabolic waste.

Quantitatively, water is the main constituent of the organism. In an adult man of average size (70 kg) it represents approximately 60% of the body weight, i.e. about 40 kg.

The water present in our organism is divided into two compartments, the intracellular one (2/3 of the total volume) and the extracellular one (comprising plasma, lymph, interstitial fluid and cephalorachidian one).

The liquid compartments of the organism are separated from each other by semipermeable membranes. The plasma, for example, is separated from the interstitial fluid through the walls of the blood vessels. Cell membranes, on the other hand, prevent direct contact between the interstitial and intracellular fluids.

In fact, it is essential for the organism to maintain the volumetric homeostasis of the two compartments.

Body water is mainly distributed in non-adipose tissue and constitutes about 72% of the lean mass

The volume of the intracellular liquid depends on the concentration of the solutes in the interstitial one. Under normal conditions, interstitial and intracellular fluid are isotonic, that is, they have the same osmolarity. If the concentration of the solutes were greater in the intracellular liquid, the cell would swell by osmosis; in the opposite situation, the cell would tend to shrivel up. However, both circumstances would be seriously damaging to cellular structures.

The volume of the plasma, called volemia, must also be kept constant to ensure good cardiac function. In fact, if there is an increase in plasma volume, blood pressure increases (hypertension); on the contrary, in the presence of hypovolemia, the pressure decreases, the blood viscosity increases and the heart gets tired.

To ensure homeostasis of the volume of intracellular and intravascular fluids, it is necessary to keep the body's water content constant. In order for this balance to occur, the balance between water inflows and outflows must be balanced.

With very few exceptions, foods contain a non-negligible amount of water.

(% of edible part)

From: food composition tables. INN, 1997

The water balance is kept in balance through the regulation of outputs (by changing the volume of urine excreted) and through the control of inputs (by changing the water intake).

In basal conditions, about 60% of the daily loss of water occurs with urine. The increase in temperature and physical exercise increase water losses through sweating and numb perspiration.

To compensate for these exits, the body reduces the volume of urine eliminated, increasing the secretion of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) or vasopressin. This peptide, secreted by the posterior pituitary, acts in the kidney, where it promotes the reabsorption of water, consequently reducing its elimination in the urine.

The regulation of income, on the other hand, is implemented through the stimulation of thirst, which is activated when the blood volume decreases (dehydration) or when the body fluids tend to become hypertonic (after a salty meal).

Dehydration

Dehydration, even if modest, is a dangerous condition for the organism. A 7% decrease in total body water is in fact sufficient to endanger the very survival of the individual.

Dehydration is dangerous for several reasons. First of all, in a dehydrated body the mechanism of sweating is blocked, in order to save the little water left in the body. However, the lack of sweat secretion causes a considerable organic overheating, with negative repercussions on the hypothalamic thermoregulatory center (see heat stroke).

Furthermore, in a dehydrated organism the volume is reduced, so that the blood circulates less well in the vessels, the heart becomes fatigued and, in extreme cases, cardio-circulatory collapse may arise.

The causes of dehydration are many:

exposure to a dry and breezy climate, not necessarily hot (even at low temperatures dehydration is in fact considerable; cold, for example, stimulates the elimination of water with the urine. In addition, in the mountains, more water is eliminated by breathing , since the vapor pressure of the exhaled air is higher than the ambient one).

Intense and prolonged exercise.

Repeated episodes of vomiting and abundant diarrhea (in case of cholera the death of the individual occurs precisely because of the considerable water losses linked to an unstoppable diarrhea).

Heavy bleeding and burns.

An "insufficient intake of liquids (especially in the elderly, because they are less sensitive to the stimulus of thirst).

How much should you drink?

Listen on Spreaker.In general, it is recommended to drink at least one and a half liters of water a day.

It is particularly important to increase the water intake during the summer months and when doing sports, in order to recover the water lost in sweating.

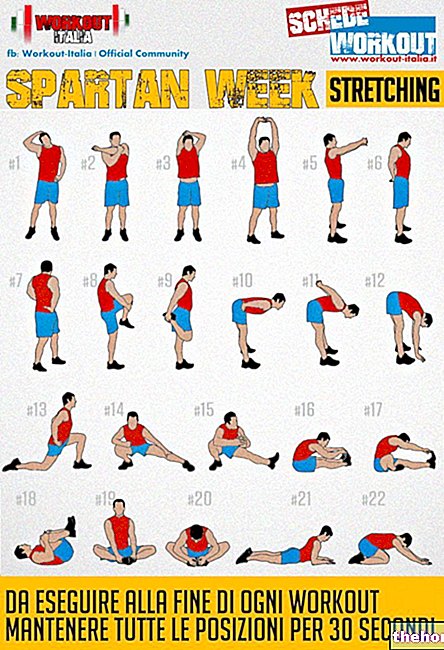

To prevent dehydration when exercising, drink before, during and after exertion. In particular, when physical exercise is prolonged, water alone may not be enough. For this reason it is advisable to add a modest quantity of carbohydrates and mineral salts (especially sodium, chlorine and potassium) to the drink. The concentration of carbohydrates in the drink is not in any case, it must be higher than 8%, to avoid increasing the osmolarity of the solution, with consequent recall of water inside the digestive tract (opposite effect to that hoped for). This minimum percentage is however important to supply glucose to the " organism, saving the precious hepatic and muscle glycogen reserves.

.jpg)