The uterus is the female genital organ which:

- welcomes the fertilized egg cell and guarantees its development, providing it with all the necessary nourishment during the nine months of pregnancy

- favors the expulsion of the fetus at the time of delivery.

To perform these functions, the uterus undergoes cyclical changes that reflect the hormonal status of the woman.

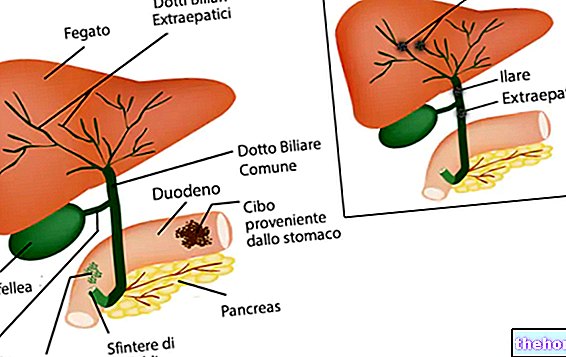

The uterus is an uneven and hollow organ, placed in the center of the small pelvis. It has relations with the bladder (anteriorly), with the rectum (posteriorly), with the intestinal loops (above) and with the vagina (below).

The internal cavity of the uterus, its shape and the macroscopic characteristics of the organ, vary slightly from subject to subject. In addition, over the course of life, the woman's uterus undergoes morphological and histological alterations in relation to numerous factors, both physiological (age, constitutional biotype, null or multiparity, period of the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, puerperium) and iatrogenic (hormonal therapies , surgical interventions and their outcomes) or pathological.

In the child and in the prepubescent, the uterus has an elongated, glove-like appearance.

In the adult woman it assumes the shape of an "inverted pear".

In post-menopause and in senile age, the volume of the uterus gradually decreases and takes on an elliptical and flattened shape.

The uterus of an adult woman has the shape of an inverted pear, with the widest part at the top and the narrowest at the bottom, where it interacts with the vagina. It has an average length of 7-8 cm, a transverse diameter of 4-5 cm, and an antero-posterior diameter of 4 cm; the weight is 60-70 g.

At the end of pregnancy, the total volume of the uterus can increase up to 100 times compared to the initial one and, overall, its weight reaches 1 kg.

In the multipara, or in the woman who has had children, the triangular shape (inverted pear) is somewhat lost, since the uterus takes on a more globular aspect.

From a macroscopic point of view, the uterus is didactically divided into at least two regions, which have different structures, functions and diseases:

- body of the uterus: upper portion, more expanded and voluminous, about 4 cm long, it rests on the urinary bladder

- neck of the uterus or cervix: lower portion, smaller and narrower, about 3-4 cm long. It is facing downwards, that is, it looks towards the vagina where it protrudes through the so-called "tench snout".

in addition to these regions, the following are also identified:

- isthmus of the uterus: narrowing that divides the body and neck of the uterus

- fundus or base of the uterus: portion of the uterine cavity located above the imaginary line that joins the two fallopian tubes, facing forward

As shown in the figure, the relationship between the body and the neck of the uterus also varies with age: in the prepubertal phase it is in favor of the neck (longer); over the years this ratio is reversed: at the menarche it is 1: 1 and then the body begins to exceed the neck both in terms of size, height and volume.

The first figure of the article, in addition to the relationship with the neighboring organs, shows us the anatomical location of the uterus: The body is inclined on the neck with an anterior angle of about 120 degrees which gives rise to the antiflexion of the uterus; with the axis of the vagina, the neck forms an angle of about 90 degrees called anteversion. Overall, in normal conditions, the uterus therefore assumes an antiflex and antiverse position. → In depth: retroverted, retroflexed or retroverted uterus

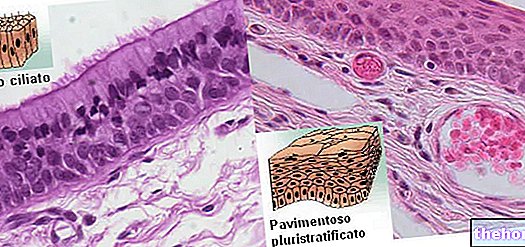

Histology and changes in the endometrium during the menstrual cycle

The uterus is an extremely dynamic organ, not only in the adaptations of shape and structure, but also from the point of view of the cells and tissues that compose it.

In the wall of the uterus we can recognize three important layers of tissue:

- endometrium (mucous membrane): superficial layer facing the uterine cavity; rich in glands, it is subject to periodic variations during the menstrual cycle

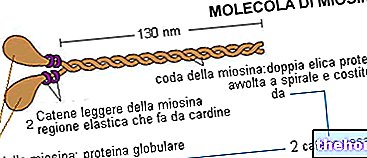

- myometrium (muscle layer): underlying layer, thicker, made up of smooth (involuntary) muscle tissue; it allows the uterus to dilate during pregnancy; at the moment of delivery, under the influence of oxytocin, it contracts to favor the birth of the newborn.

- Perimetry (serous tunic): peritoneal sheet of lining, missing in the sides and supravaginal portion of the cervix

The uterus (in particular its innermost layer or endometrium) is therefore the organ from which the periodic menstrual flow derives during a woman's reproductive age. From puberty (11-13 years) to menopause (45-50 years) ), the endometrium of the body and fundus undergoes cyclical changes that occur every 28 days (approximately) under the influence of ovarian hormones:

- regenerative and proliferative phase (days 5-14): the uterine endometrium is gradually enriched with new cells and blood vessels, the tubular glands lengthen and overall the endometrium increases its thickness

- glandular or secretory phase (days 14-28): in this phase the endometrium reaches its maximum thickness, the cells enlarge and fill with fat and glycogen, the tissue becomes edematous → the uterus is functionally and structurally ready to accommodate the cell fertilized egg and to support it in its development;

- menstrual phase (days 1-4): the constant maintenance of the endometrium in a favorable state for implantation would be, for the organism, too expensive from an energy point of view. For this reason, in the event that the egg cell is not fertilized , the most superficial layer of the endometrium undergoes necrosis, flaking off; the leakage of small quantities of blood and tissue residues by now dead gives rise to the menstrual flow.

PLEASE NOTE: at the level of the neck of the uterus, the mucosa does not undergo cyclical changes as striking as those described above. What varies is above all the mucous secretion of the cervical glands:

- generally very dense, to the point of forming a real plug that hinders the ascent of the spermatozoa in the cervix, it becomes more fluid in the days between ovulation, ensuring easier access to the uterine cavity for the sperm.

The mucous secretion of the uterine cervix also protects the innermost genital organs from ascending infections. During pregnancy, the uterine cervix also functions as a mechanical support to prevent the premature exit of the fetus favored by the force of gravity. Only at the moment of birth, while the uterine myometrium contracts under the stimulus of oxytocin, the cervix relaxes for letting the fetus out to full term.

.jpg)